"HISTORY"

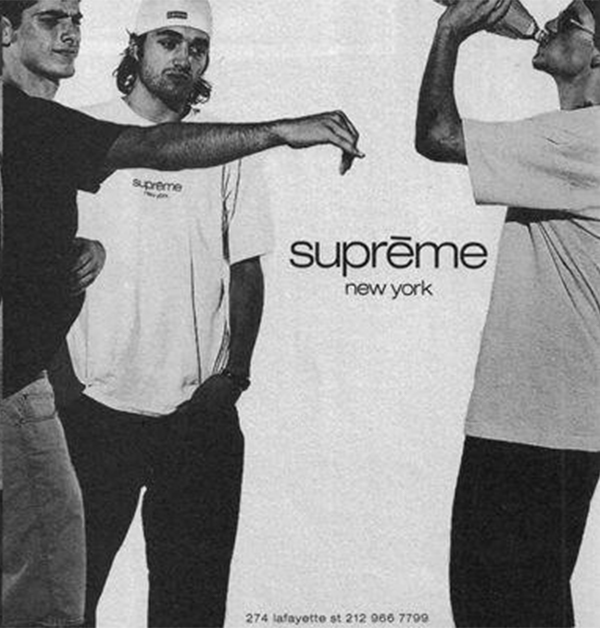

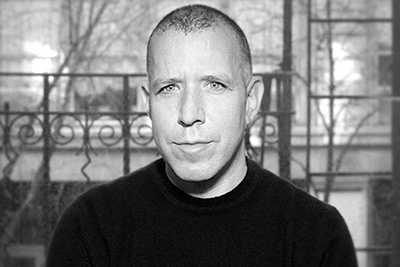

James Jebbia, the man who, in 1994, founded and to this day runs the SoHo-based company that has been making clothing and skateboards and a lot of other things that the people who love it absolutely have to have, doesn’t think of Supreme the way most people in fashion might—as a brand that started out in a small store on Lafayette Street and has since inched its way to legendary global status. He thinks of Supreme more as a space. When Jebbia was a teenager in Crawley, West Sussex, in the eighties, working at a Duracell factory, listening to T. Rex and Bowie on breaks and spending his spare cash on trips to London to buy clothes, it was always in a certain elusive kind of store—one that became the model for Supreme.

“The cool, cool shop,” says Jebbia, who is 54 and dressed in jeans and a plain dark-blue T-shirt, label-free and low-key, with closely cropped hair and deep blue eyes. “The shop that carries the cool stuff that everybody was wearing—no big brands or anything.”

His office a few blocks west of the Supreme store is adorned with a skateboard designed by Raymond Pettibon; some drawings by Jebbia’s kids, age 8 and 10; and a larger-than-life-size portrait of James Brown—whom Jebbia, crucially, sees as not just the hardest-working man in showbiz but as a guy who never played down to his audience. Jebbia is, likewise, ever-mindful of his customer, who is generally aged eighteen to 25 and wants simply to buy cool stuff—and who will pay for it, assuming it’s worth it.

Of course, what began as a generally male-focused enterprise has, with more and more frequency, been co-opted by women—mirroring both the rise of girl skaters and youth culture’s impressively genderless approach to dressing and living. (The recent surfeit of off-duty models posting Instagrams of themselves lounging, living, and partying in Supreme has only added fuel to the fire.)

“My thing has always been that the clothing we make is kind of like music,” Jebbia says. “There are always critics that don’t understand that young people can be into Bob Dylan but also into the Wu-Tang Clan and Coltrane and Social Distortion. Young people—and skaters—are very, very open-minded . . . to music, to art, to many things, and that allowed us to make things with an open mind.”

“When you see the lines for Supreme in New York or London,” says Jones, “you see so many different types of people, and they are people you can relate to—they understand high-low, they’re smart, they’re intelligent, and they’re humorous. They know what they want, and they are very loyal—and a customer who is loyal is a real aspiration for anybody with a brand.”

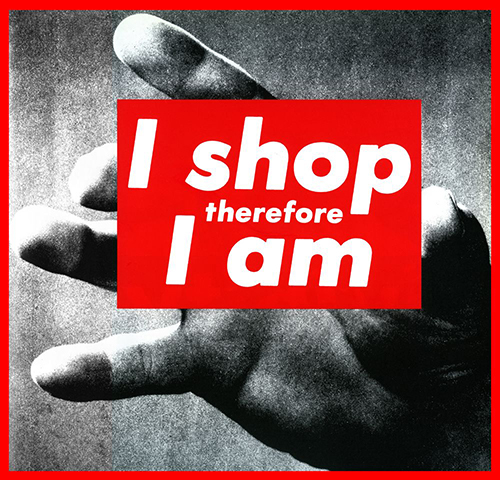

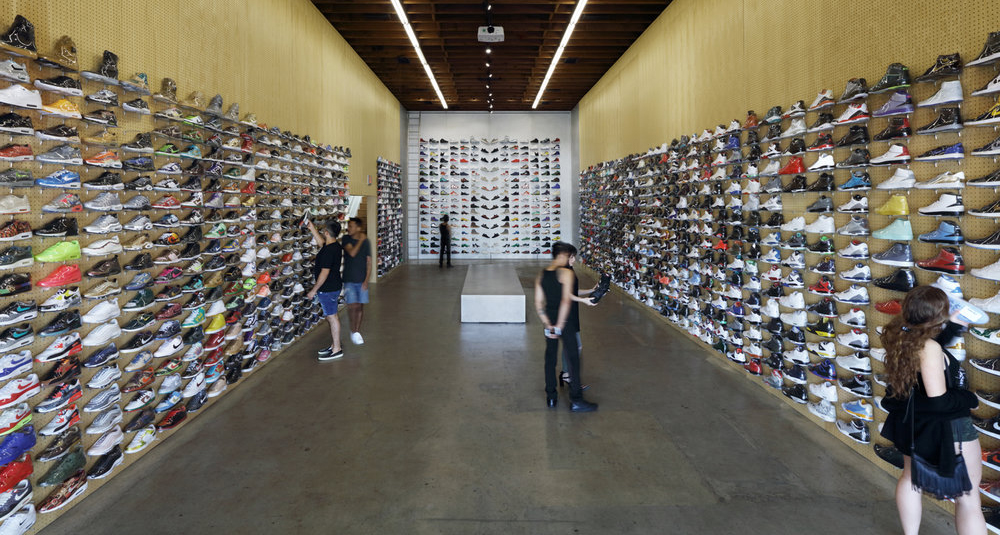

The Vuitton collaboration was also, for many in fashion, their first glimpse into the secretive world of Supreme, which has become a kind of shorthand for authenticity, immediacy, speed, and deftness in its way of doing business. More than just selling sweats and tees and hats, the brand brings out a new collection two times a year, like any fashion company—generally, an online look-book, followed by a few pieces dropped every Thursday, each item available both online and in the stores. A Supreme drop, for those who haven’t experienced it, is an event. “We can have a leather jacket for $1,500, and if it’s a good value, young people will understand that,” Jebbia says. “But we also want to have the feeling that this won’t be here in a month. When I grew up, I think everybody felt that way. It’s like, If I love this, it may not be here, so I should buy it.”

If Jebbia was anxious to get press when he started, now he worries about overexposure. Supreme keeps advertising to a minimum and works with people like Sage Elsesser, the pro skater, who models for its look-book. Elsesser is the kind of person marketers think of as an influential outsider but whom customers see as just a cool skater. “Supreme is family-oriented, and that matters most to me,” says Elsesser. Supremeheads understand the nuances of marketing nonsense; their nose, both for corporations pretending to be human and for brands trying to throw themselves at potential customers, is highly refined, a reason Supreme uses social media primarily as an exhibit space. “We’re not trying to overconnect ourselves,” Jebbia says. “We’re just trying to show people things that we do—no different from what a magazine did 20 years ago.” (They published six issues of their own magazine before developing their website around 2006.)

Nothing about Supreme was planned in advance, its success a coincidence of place, time, and hard work. By the time he was nineteen, Jebbia had left England and was a sales assistant at a SoHo store called Parachute. From there, he worked a table at the nearby flea market, then founded a store, Union, on Spring Street that sold British goods and streetwear. Union did well enough until it began to sell clothing designed by Shawn Stüssy, the skateboarder and surfer, at which point it did great. Next, Jebbia helped run a shop with Stüssy until Stüssy decided to retire. “Now what the hell am I going to do?” he recalls asking himself.

“I always really liked what was coming out of the skate world,” Jebbia says. “It was less commercial—it had more edge and more fuck-you type stuff.” So he decided to open his own skate shop on Lafayette Street. Lafayette was then a relatively quiet strip of antiques stores, a firehouse, and a machinist, but also a Keith Haring shop—a downtown art-scene connection that, in hindsight, was key. Jebbia built a spare space (the very notions of spare and clean soon becoming Supreme trademarks), then brought in good skateboards, cranked the music, and played videos constantly—wildly disparate things like Muhammad Ali fight videos and Taxi Driver—to draw onlookers.

The kids he employed, often skateboarders themselves, were cool, opinionated—and, yes, often scowling at the uncool—but allowed outsiders a view into their clique. The very first employees were extras in Larry Clark’s film Kids, written by Harmony Korine, who lived in the neighborhood and recalls Supreme as less of a store, more of a hang—though within a year, designers from uptown as well as Europe and Japan were paying attention. “They were easy adapters to a kind of dissonance, where you have several things at different points on the cultural spectrum that are all connected by a kind of aesthetic or vibe,” says Korine. Supreme started a magazine featuring the faces of the young downtown scene—Chloë Sevigny, Ryan McGinley, Mark Gonzales—a mix of models, artists, skaters. “James tapped into a secret sauce,” Korine continues, “and they’ve kept strong because youth propels the culture, and they are always on the side of the youth. You can’t fake that.”

Initially, Supreme made only a few T-shirts. Then their customers arrived wearing Carhartt matched with Vuitton, Gucci with Levi’s. Soon Supreme tried a cotton hoodie, realizing that if it was simply made a little better than what was out there, skaters would be willing to pay a little more for it. According to Jebbia, this sort of thinking isn’t unique to skate culture. “Gucci is saying, ‘Hey—just because you’re young doesn’t mean you won’t love this $800 sweatshirt,’” he says. Jebbia can’t say enough about designers who respect young buyers rather than simply use them to attract press. The genius of Alessandro Michele, Gucci’s creative director, as he sees it, is that he doesn’t just show young people wearing pieces on the runway; he hopes they’ll actually wear them as they go about their lives. “He’s creating exciting products for right now—today,” Jebbia says.

The hoodies worked, as did the fitted caps they tried next. Collaborations came early on, with artists making work for skateboard decks, as well as for T-shirts and other clothing. The painter Lucien Smith credits Supreme’s intimacy. “A lot of people don’t understand that this is a supersmall group of people who are just working on that original idea—that it is a skate shop,” he says.

The list of artists who have worked with Supreme over the last two decades could fill a gallery space: Christopher Wool, Jeff Koons, Mark Flood, Nate Lowman, John Baldessari, Damien Hirst—even Neil Young. But the collaboration that changed everything was the line of tees, shoes, and shirts produced with Comme des Garçons, in 2012. “I think that opened a lot of doors, a lot of eyes,” Jebbia says.

“I have never met anyone with such a strong, single-minded vision who has always stayed close to his sense of values,” says Adrian Joffe, president of Comme des Garçons and Rei Kawakubo’s husband. “That’s why our collaboration was so meaningful—and why the growth of Supreme has in a way mirrored our own.”

Spend some time with Jebbia and you get to know his own favorite brands, which include well-known names like Patagonia along with a few you are not likely to have heard of, like Antihero, a skateboard company. “They’re very below the radar,” he says, “but they are very pure in what they do—I hold them in as much esteem as I do Chanel or Vuitton.”

I think a lot of brands reach a point where they say, We kind of have a formula—we’ve got it made,” he says. “Our formula is there’s no formula.” He mentions his wife, Bianca, who grew up in Elmhurst, Queens, in a Chilean family and raises their children at their apartment in Lower Manhattan. “She’ll shop at Prada, she’ll shop at Chanel—and then she’ll shop at Uniqlo and she’ll wear something from Supreme,” Jebbia says. “And it’s not ‘Look at me dumbing this stuff down.’ She’s just wearing what she likes, and I think that people are more like that now.”

On one recent morning in his office, Jebbia stepped up from his desk and went out for coffee, passing through the studio from which the new Supreme motorized street bike was about to drop, the latest in the seemingly infinite collaborations—this one with Coleman. The space is big and open and white-walled and has the feeling of a workshop. The office staff—an industrious, no-frills team of about 40—is dressed elegantly but practically as they prepare to release their new Comme des Garçons Nike Air Force 1s, the long lines on Lafayette Street still a day or two from forming.

Out on the street, he offered a tour through his own history. “Parachute was there,” he says, “and Comme des Garçons had a store there. . . .”

He pointed up. “I love that Alex Katz lives up there,” he says. “People can talk shit about the neighborhood, but I really think it’s one of the most vibrant places in the world.”

Jebbia doesn’t have a title. “My wife keeps saying I should just call myself founder, but I don’t know,” he says. “ ‘Just tell em I run a skate shop’ is how I usually put it. But I guess I kind of direct things.” He likes to stay out of categories, to be free of market demands. Growth, for instance, is something he is focused on, but at the Supreme pace: slow, but quick enough to satisfy customer demand. “We don’t want people to think we are a tricky, hard-to-get brand,” he says. “We can only do so many things,” he says. “The hat factory we use can only make so many hats.” Jebbia is also wary of anything that will raise his overhead or put his ability to take risks at risk. “We’re making stuff we’re proud of,” he says, “not doing stuff to stay alive. I don’t think enough people take risks, and when you do, people respond—in music, in art, in fashion.”

As we walk, Jebbia is greeted by people from the neighborhood, and when at last we sit he seems to almost relax for a minute talking about his weekends—which are, he stresses, decidedly unglamorous. “The kids have a lot of homework,” he says, “and I actually like not having any plans.” As with his stores, he likes to keep life clean and simple—dinner with his wife and kids, and maybe a weekend visit to MoMA. “I don’t have this lavish lifestyle,” he says, “so I don’t have this massive overhead.”

And with that, he’s back to being wary. “I’ve seen brands get comfortable,” he says, “but I’ve never felt comfortable. I’ve always felt every season could be our last.”

written by Robert Sullivan for Vogue Magazine, August 10, 2017