"HISTORY"

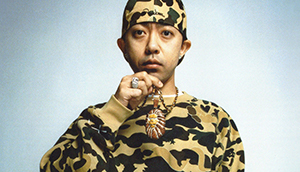

Like most of the Japanese streetwear icons, BAPE’s roots can be traced back to the ura-Harajuku scene of the early ’90s. Most of today’s heavyweights — Shin Takazawa of Neighborhood, Tetsu Nishiyama of WTaps, Hiroshi Fujiwara, Sk8thing and so on — were actually a group of friends in the same scene, each doing their own thing and helping each other out along the way.

After a few years working as an editor and stylist at Popeye magazine, Nigo opened up his store ‘Nowhere’ with Jun Takahashi of Undercover, and shortly after worked with Sk8thing to launch his own clothing brand, A Bathing Ape — or BAPE.

Nigo is a notorious fan of 20th century pop culture, and channelled his love for the 1968 film Planet of the Apes in the name, as well as referring to the Japanese idiom ‘A bathing ape in lukewarm water.’ The phrase is used to describe somebody who overindulges, like lying in a bath until the water isn’t even hot anymore, so was an almost tongue-in-cheek reference to the same hyper-consumptive youth that would eventually form the cornerstone of his brand.

With its mixture of imported American street and sportswear and pioneering Japanese streetwear labels like WTaps-predecessor Forty Percents Against Rights, Nowhere quickly became a cornerstone of the burgeoning ura-Harajuku scene, with Nigo as one of its figureheads.

Alongside Neighborhood, Hysteric Glamour and other such brands, A Bathing Ape and Nowhere helped to define the “Urahara” style of the ’90s. Urahara comes from the term ‘ura-Harajuku’ which basically means “underground Harajuku” – the underground scene going during the early ‘90s which was heavily informed by a mixture of various American clothings and styles.

Through associations with the International Stüssy Tribe and James Lavelle of UNKLE & Mo’Wax records, BAPE was quickly established as a cultural tastemaker in Tokyo, as well as a best-kept secret in closed circles abroad – someone’s friend would go to Japan, bring back some clothes and a few magazines, and the hype would slowly spread through word of mouth alone.

The original reason for BAPE’s scarcity was arguably one of financial necessity – Nigo started out on a tight budget and only afford to produce around 50 T-shirts a week – but he also disliked the idea of everyone wearing the same thing.

By 1998 the brand was stocked in around 40 locations across Japan, but Nigo then made the bold move of canceling all wholesale operations, instead focusing all of his energy on a single flagship location in Tokyo. Sales quickly exceeded their previous levels and the fundamental streetwear formula of hype, scarcity and public spectacle was born — and arguably birthed streetwear’s queuing culture that we know and love (or loathe) today.

The late ’90s to early ’00s are generally cited as the golden era of BAPE, with product rapidly selling out in Japan and fashion-savvy figures like The Notorious B.I.G. giving the brand some healthy kudos in hip-hop culture. In the early ’00s Nigo was introduced to Pharrell Williams through Jacob the Jeweller, who noted the two’s similar tastes in jewelry commissions.

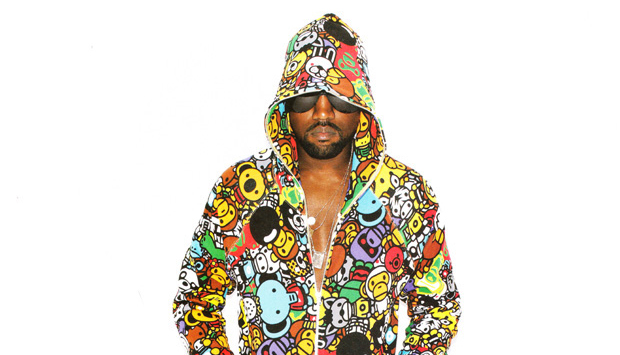

Well-known for his laidback persona and youthful free spirit, BAPE’s bright and flashy aesthetic fit perfectly with Pharrell’s personal style, and his success was coupled with a greater attention being paid to BAPE stateside, though the brand remained scarce due to the absence of American stockists.

In 2005, Pharrell and Nigo partnered up on the N*E*R*D frontman’s Billionaire Boys Club & Ice Cream clothing lines, and the flashy, playful and oversized aesthetic of BAPE became a mainstay of millennial hip-hop fashion. In 2005 and 2006, BAPE’s first overseas flagship stores were opened in New York and Los Angeles, and Kanye West designed his own pair of the brand’s coveted Bapesta sneaker.

Then, in 2007, the notorious video for Soulja Boy’s ‘Crank Dat’ was released, featuring Soulja Boy’s own Bapestas heavily (though their authenticity has been called into question) along with the line, ‘I got me some Bathin’ Ape’. That was it; BAPE entered the cultural zeitgeist and claimed its throne as the pinnacle of flashy, expensive streetwear.

Though the BAPE story wouldn’t be the same without its meteoric rise to success in the States, the brand’s newfound popularity brought with it a number of problems. Scarcity of product in the U.S., combined with BAPE’s unusually high prices for young western consumers, led to the proliferation of counterfeit product, saturating the market before the brand could find its feet. BAPE’s relatively-sudden explosion also meant that its popularity became more of a fad or passing trend than the slow and carefully-cultivated hype that it had built in Japan.

By 2010 the brand had fallen out of vogue, and it emerged that A Bathing Ape had amassed over 2.5 billion yen ($22.5 million) in debt. Nigo stepped down from the company as CEO, and in 2011 the brand was sold to Hong Kong fashion conglomerate I.T for a paltry $2.8 million. Over the next two years Nigo stayed with the company to assist with the transition, launching his new vintage-inspired label Human Made and taking on a new role as Creative Director of Uniqlo’s ‘UT’ T-shirt line.

Since its acquisition by I.T, BAPE has settled as a mainstay label of contemporary streetwear; though the brand is nowhere near as scarce and unpredictable as it used to be, its legacy as one of the original streetwear icons, as well as its deep connections in hip-hop and street culture, has seen the brand endure with a much broader audience.

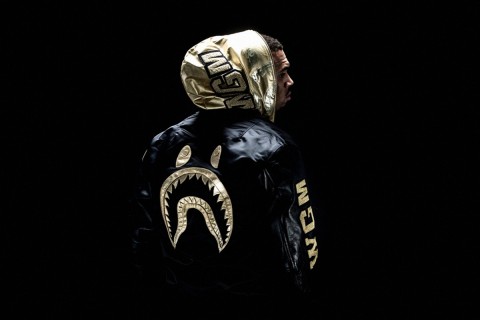

Once-coveted rarities like BAPE shark hoodies and insulated snow jackets have become mainstay pieces every season, and the brand’s iconic camo is now one of the most prolific graphics of contemporary street style. To many of the older heads, the BAPE of today has little in common with its roots, but whether that’s a good or bad thing is, frankly, a matter of perspective. In 2017, it’s still a brand defined by its young, consumptive audience’s voracious appetite for anything on offer, so in many ways it’s the same as it ever was.

An excerpt from an article on highsnobiety.com