Español 343 U (CRN 45108)

(Intro. Hispanic

Literature)

Invierno

2006; 4 créditos; sección 001

Instructor: Dr. Oscar Fernández

Clase: martes y

jueves, 16:40-18:30

Oficina: NH 451 Q

BHB

220

Correo electrónico:

Horas de oficina: martes

y jueves,

http://web.pdx.edu/~osf/

14:00-15:00 y por cita

Descripción del curso

Español 343 U aportará una

introducción a la genealogía de movimientos literarios en las Américas

comenzando en el siglo XIX. El enfoque

del curso será introducir al estudiante a la filosofía de varios

movimientos

literarios y obras representativas de

estos mismos. El estudio de la literatura y los movimientos literarios

se

concentrará en la presentación escrita y oral de investigaciones hechas

por los

estudiantes.

Objetivos

del curso

*Practicar

formas escritas del español en una variedad de géneros y

contextos.

*Proveer

al estudiante con una variedad de lecturas representativas

que desarrollen un nivel avanzado de español.

*Entender

el desarrollo de movimientos literarios.

*Interpretar el punto de vista

de una lectura y discutir polémicas relevantes.

*Interpretar y expresar una

opinión, tanto oralmente como por escrito.

*Preparar a los estudiantes a

dar presentaciones con índole académico y literario.

*Apreciar

la rica variedad de

culturas y literaturas en las Américas.

Textos

requeridos*

Garganigo, John

F., ed. et al.

Huellas de las literaturas

hispanoamericanas. Upper

Saddle River,

NJ:

Prentice

Hall, 2002. [Huellas]

*Por

favor traer todos los textos cada día.

Textos

recomendados

Diccionario

de bolsillo y comprar

una versión reciente del MLA Handbook

for Writers of

Research Papers

o

también usar esta página electrónica, “MLA Style

Guide”:

<http://www.lib.usm.edu/research/guides/mla.html>.

Preparación

para la clase

Se le ofrece al estudiante la

siguiente guía para establecer el mínimo de horas de estudio afuera de

la

clase:

4

créditos x 3 horas de estudio = 12 horas mínimas de tarea.

Evaluación

Participación: Mirar la página

electrónica para leer los detalles (pulsear “Participación”).

Asistencia: El estudiante

es responsable de completar todas las asignaturas durante su ausencia. Ausencias múltiples resultarán en un cero en

participación y una F para el curso: mirar la página electrónica para

leer los

detalles.

Composiciones: (2). Dos

composiciones con la posibilidad

de hacer una revisión del trabajo inicial.

Cada composición tendrá un mínimo de 600 palabras o por

lo menos

100 líneas de texto. Todo trabajo entregado tarde

recibirá –2 puntos por día (ojo: los fines de semana cuentan

como dos

días). El instructor no es responsable si el estudiante deja su

composición en

el casillero del departamento (office

mailbox) o debajo de la

puerta de mi oficina. No se recibirán

composiciones vía el Internet

(por favor no mandar attachments.) El tema de las composiciones estará basado en

tópicos y textos discutidos en clase.

Cada composición tiene que tener un argumento, seguir el formato

del Modern Language Association

(MLA)

e incluír una página de referencias (Obras

citadas en la última página de cada

ensayo). Las composiciones no son book reports ni

son ensayos biográficos de los autores en nuestras lecturas. Durante la última semana del curso, el

estudiante tendrá que hacer una breve presentación (de 5-8 minutos)

sobre sus

investigaciones sobre composición final.

Formato para

todas las composiciones: All drafts for the composition must

be handed in together and follow MLA (Modern Language Association)

guidelines. They must be numbered and

stapled. All drafts and copies for

compositions must

be typed using a font size 12, Times New Roman, double-spaced, in black

ink,

with the student's name, the composition title, the draft number, word

count

and the date the assignment is due on the top of the first page. Each

page must

have last name and page number as shown below.

Please check website for a model of how all compositions should

appear.

López

1

Juana

López

Spanish

343 U. Sec. ___

Composición #

_______

20 de octubre

(month in lower case) de 20xx

# de

palabras

Masculinidad

y nacionalismo en “El

matadero”*

*Do not

write the word “title,” do not

underline, bold, or italicize the title.

Title must summarize the thesis of your composition. Please, no embellishments in the title (no

colors, different fonts, for example).

Diacritics: Students must

incorporate computer-generated

diacritics in their textual documents. Check web

page

for commands

in Microsoft

Word. No se aceptarán

composiciones con tildes escritas a mano.

Presentación y

resumen analítico: El estudiante dará una breve presentación sobre un

artículo reciente de crítica sobre uno de los textos en este prontuario. El estudiante entregará su

resumen por escrito siguiendo el siguiente

formato del MLA. The write-up is due on the day

of the presentation and

the presentation must coincide with the order of readings in the

syllabus.

Juana

López

Spanish 343 U Sec.

___

Composición

# _____

20 de

octubre (month

in lower case)

de 20xx

# de palabras

Foster, David

William. “Procesos significantes en ‘El

matadero’.” Para una lectura

semiótica del ensayo latinoamericano. Madrid:

José Porrúa

Turanzas, 1983.

5-18.

In

essay and third-person format, please answer the

following:

1.

Resumen.

¿Cuál es el argumento? ¿Qué

evidencia crítica usa el crítico

para establecer su argumento?

2.

Relación con el texto literario.

¿Qué evidencia del texto (el cuento, la

novela, el poema, por ejemplo) usa el crítico para interpretarlo?

3.

Conclusión.

¿Cuál es la importancia de esta crítica?

¿Cómo nos ayuda entender el

texto? ¿Cómo podemos usar la obra

crítica en la discusión de la clase?

¿Dónde puedo

encontrar recursos secundarios para mi presentación y resumen? Además de usar recursos

usando el banco de datos de nuestra biblioteca, al final de cada

lectura en Huellas hay una sección llamada

“Bibliografía.” El estudiante puede usar

cualquier libro, artículo, o reseña en esa lista. OJO:

Búsquedas en “Goggle”

no serán aceptadas.

Formato y

elementos requeridos para la propuesta no. 1 y no. 2:

Juana

López

Spanish 343 U Sec. ___

Propuesta #

_____

20 de

febrero (month

in lower case)

de 20xx.

INSERT TITLE HERE: Incluir un título que

describa el argumento

principal

In

essay and in third-person format, answer the

following questions. Do not individually

answer each question in question/answer format.

Instead, your proposal, like your paper, needs to have an

introduction,

a thesis, presentation of primary and secondary sources, and a

conclusion:

1.

What is the

question you want to answer as it relates to the primary text (s)? What have others (critics, authors, the

textbook, for example) written about your problem/case?

2.

What primary

sources (novels, poems, plays, for example) will help you answer your

question? Give at least one example of how

the selected

primary sources answer this question.

3.

What

secondary sources (works of criticism, for example) will help you

support your

answers? Give at least one example of

how your secondary sources help answer this question.

4.

In short,

what is your argument (your thesis)?

5.

What

preliminary conclusions do you have at this time? [Think

if your case/problem connects with

broader problems in literary studies, in culture and the arts, in

society?]

6.

In a separate page and with the title of Obras citadas, write in alphabetical order the list of texts you will use

in your

composition using MLA conventions. This

page can be written entirely in English.

¿Dónde encuentro temas para

las propuestas?:

Después de cada lectura en Huellas hay una sección con

preguntas temáticas llamada “Reflexión

y análisis.” El estudiante puede

seleccionar una de esas preguntas como la base de su primera propuesta

y

composición.

Formato y

elementos requeridos si propuesta no. 2 es una revisión del trabajo

anterior:

Seguir el

mismo formato dado anteriormente. Si el

estudiante desea hacer una revisión de su primera composición para su

segundo

trabajo, la segunda propuesta tendrá las

siguientes secciones:

1.

Título. ¿El

título ha cambiado? Give a new title

that shows how you have changed your thesis.

2.

Textos primarios.

¿Hay nuevos textos primarios? Show why you

are adding new texts to make your case.

3.

Tesis. ¿Cómo

ha cambiado el argumento? Explique cómo

esta composición cambiará?

Show

how you are changing

your argument.

4.

Textos secundarios.

¿Cuáles textos adicionales usarás?

What ideas

from these additional texts will you be using in the

composition? Please cite new

references in the

Obras citadas page.

5.

In a separate

page and with the title of Obras citadas,

write in alphabetical order the list of texts you will use in your

composition

using MLA conventions. This page can be

written entirely in English.

Formato para la presentación al final

El

título del ensayo

- Tesis. ¿Cuál es el argumento? ¿Qué

evidencia crítica usas para

establecer el argumento? ¿Cuáles

son los textos primarios que ayudarán a responder el argumento?

- Relación con texto (s) primario (s).

¿Qué evidencia del texto (el cuento, la novela, el poema,

por ejemplo) ha sido empleada para evaluar la tesis?

- Relación con texto (s) secundario (s). Give at least one example of

how your secondary sources help answer your thesis.

- Conclusión. ¿Cuál es la

importancia de esta crítica? ¿Cómo nos

ayuda entender el texto y sus contextos? ¿Cómo podemos usar los “resultados” de la

presentación para entender problemáticas más globales relacionadas al

texto?

Correo

electrónico: Para

recibir una respuesta usando el correo electrónico, por favor

reservar por lo menos 48 horas de lunes a viernes.

Preguntas antes del día de asignaturas (o

pruebas) no serán respondidas. Todo estudiante debe usar su propio

correo

electrónico: para asegurar la privacidad de todos los estudiantes, el

instructor sólo responderá a correos electrónicos que

provienen de la cuenta del estudiante. Para

mantenernos en mejor comunicación, es

necesario usar el siguiente formato en el subject heading

del correo electrónico:

Subject: Class/Section/Student’s

name/Assignment or

Type of Question

Subject: Span

343 U/Sec 001/Juana López/Composición #1

Donde localizar las notas: Todo trabajo

será entregado durante el período de clase.

Normalmente no se darán notas por medio del Internet o por

teléfono. Las notas también no se

pondrán afuera de la oficina. Es la

responsabilidad del estudiante de estar pendiente de su nota durante el

trimestre

y de reunirse con el instructor cuando hay preguntas. El instructor no dará

estimaciones de la nota durante el período de clase.

Si hay preguntas sobre la nota de una

asignatura, el estudiante debe hacer una cita con el instructor.

Página electrónica: Es la

responsabilidad del estudiante de

mirar la página electrónica ya que esta tendrá las noticias más

recientes sobre

el curso.

Como

calcular la nota

Participación

20

Composición

no. 1

20

Composición no. 2 & breve

presentación 20

Presentación y resumen de artículo

20

Propuesta

no. 1

10

Propuesta no. 2

10

100

|

A

94-100 |

B+

87-89 |

C+

77-79 |

D+

67-69 |

F

1-59 |

|

A-

90-93 |

B

84-86 |

C

74-76 |

D

64-66 |

|

|

|

B-

80-83 |

C-

70-73 |

D-

60-63 |

|

Crédito

adicional

No

hay ningún tipo de crédito adicional en esta clase, ni durante el

trimestre ni después del final del curso.

Leyes universitarias

*

*The

following constitutes conduct as proscribed by

Portland State University for which a student or student organization

or group

is subject to disciplinary action: All

forms of academic dishonesty, cheating, and fraud, including but not

limited

to: (a) plagiarism, (b) the buying and selling of course assignments

and

research papers, (c) performing academic assignments (including tests

and

examinations) for other persons, (d) unauthorized disclosure and

receipt of

academic information and (e) falsification of research data.[2]

*Students with disabilities

need to contact the instructor as soon as possible.

The instructor will refer you to the

following PSU offices for a referral indicating how we can best help

you. It is important to obtain a referral

in order

to best accommodate your needs:

--Learning

disability screening and assessment at Counseling and Psychological

Services;

--

--Call or stop by Counseling

& Psychological Services for more information, M343 SMC,

503-725-4423.[3]

Calendario del

curso[4]

|

Semana 1 |

Introducción al

curso y fundamentos teóricos |

Tareas y trabajos |

|

10 de enero |

Introducción

al curso. ¿Qué es literatura?

¿Qué son movimientos

literarios? |

|

|

12 de enero |

Garganigo, John

F. “Romanticismo”; Heller,

Ben A. “Realismo

y naturalismo”; Gargarnigo et al. “Modernismo” (Huellas 208-18); Echevarría,

Esteban (1805-1851). “El matadero” (Huellas

228-44). |

|

|

Semana 2 |

|

|

|

17 de enero |

Library Research Day. Before coming

to Library, you need review all texts in this syllabus and select one

or two. First hour: How to do research? Second hour: Find articles. By

the end of our library tour, students should be familiar with various

search engines that will help them find resources for proposals,

papers, and presentations of articles. Students

who miss this day will need to schedule their own appointment with

Library Staff. Please see subject

librarians, <http://www.pdx.edu/library/appointments.html> |

|

|

19 de enero |

Sarmiento, Domingo

Faustino (1811-1888). Facundo

(Huellas 245-55); Gómez de Avellaneda, Gertrudis

(1814-1873). “Amor y orgullo,” Sab (Huellas 256-71). |

|

|

Semana

3 |

Modernismo

hispanoamericano. Las vanguardias |

|

|

24

de enero |

Darío,

Rubén (1867-1916). “El rey burgués,”

“Nuestros propósitos,” “Sonatina,” “Yo soy aquel,” “A Roosevelt,” “Canción de otoño en primavera,” “Lo

fatal” (Huellas 325-49); Rodó,

José Enrique (1871-1917). Ariel

(Huellas 350-58). |

|

|

26

de enero |

de Costa, René. “Del modernismo a las primeras vanguardias” (Huellas 360-61); Quiroga,

Horacio (1878-1937). “El hombre muerto” (Huellas 362-68); Vallejo, César. “Los heraldos negros,”

“Terceto autóctono,” “El pan nuestro,” “El hombre moderno,” “Poesía nueva” (Huellas 401-17). |

Entregar

propuesta no. 1 |

|

Semana 4 |

Las vanguardias. Rupturas etnocéntricas |

|

|

31 de enero |

Mistral,

Gabriela (1889-1957). “Los sonetos de la

muerte,” “La maestra rural,” “La cacería de Sandino,”

“Recado sobre Pablo Neruda” (Huellas 378-90); Neruda,

Pablo (1904-1973). Poemas 1, 5, 13, 20 de Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada, “Sobre

una poesía sin pureza,” “Alturas de Macchu

Picchu,” “José Cruz Achachalla (Minero,

Bolivia)” (Huellas 432-48). |

|

|

2 de febrero |

Slodowska,

Elzbieta. “Primeros

pasos en la ruptura de la visión etnocéntrica” (Huellas

450-53); Ortiz, Fernando (1881-1969). Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y

el azúcar (Huellas 454-62). |

|

|

Semana

5 |

Rupturas

etnocéntricas. Antecedentes a la novela y

la modernidad |

|

|

7

de febrero |

Mariátegui,

José Carlos (1894-1930). Siete

ensayos de interpretación de la realidad peruana

(Huellas 463-72); Guillén, Nicolás

(1902-1990). “Negro bembón,” “El abuelo,” “Sensemayá,” “Soldado, aprende a tirar . . .,”

“No sé por qué piensas tú” (Huellas 473-81). |

|

|

9

de febrero |

Sklodowka,

Elzbieta. “Antecedentes

de la nueva novela: entrando

en la modernidad” (Huellas 484-87);

Borges, Jorge Luis (1899-1986). “Emma Zunz,” “Borges y yo”

(Huellas 488-95). OJO: Before coming to class please have the following ready: 1. Versíon más

reciente; 2. Propuesta

no. 1. 3. Please fill

out “Checklist for Writing Papers [. . .]” (last page in syllabus). Instructor won’t read compositions if any of

these elements are missing |

Entregar composición no. 1. |

|

Semana 6 |

Antecendes al “boom.” La novela del “boom”

|

|

|

14 de enero |

Carpentier,

Alejo (1904-1980). El reino de

este mundo (Huellas 496-505). |

|

|

16 de febrero |

Sklodowska, Elzbieta. “El boom y la nueva novela” (Huellas

508-13); Cortázar, Julio (1914-1984). “Las babas del diablo” (Huellas

514-26); Rulfo, Juan (1918-1986). El llano en llamas (Huellas

527-35). |

|

|

Semana

7 |

El

“boom.” Poesía

contemporánea |

|

|

21

de febrero |

Márquez, Gabriel García (n. 1928). “Los

funerales de la Mamá Grande” (Huellas

550-67); Llosa, Mario Vargas (n. 1936). El hablador (Huellas 568-79). |

|

|

23 de febrero |

Heller, Ben A. “Epoca contemporánea: poesía y teatro” (Huellas

592-95); Paz, Octavio (1914-1998). El laberinto de la soledad; ¿Aguila o sol? (Huellas

615-24); Cardenal, Ernesto (n. 1925). “Epigramas,”

“Somoza develiza

la estatua de Somoza en el estadio Somoza,” “Oración por Marilyn

Monroe” (Huellas

636-41). |

|

|

Semana 8 |

Teatro

contemporáneo. Posmodernidades |

|

|

28 de febrero |

Garganigo, John F. “Teatro” (Huellas 596-98); Berman, Sabina (n. 1952). Entre Villa y una mujer desnuda (Huellas

652-66);

Castellanos, Rosario (1925-1974). “La

despedida,” “Linaje,” “Kinsey Report” (Huellas 627-35). |

|

|

2 de marzo |

Sklodowska, Elzbieta. “Novísima

narrativa: el post-boom y la posmodernidad” (Huellas 668-72);

Infante, Guillermo Cabrera (n. 1929). Vista del amanecer en el trópico (Huellas

673-78); Poniatowska, Elena (n. 1933). De noche vienes (Huellas

679-86). |

Entregar

propuesta no. 2. If it is a revision, please turn in first marked draft. |

|

Semana 9 |

Feminismo. Reincarnaciones coloniales |

|

|

7 de marzo |

Allende, Isabel

(n. 1942). “Tosca” (Huellas

703-14); Ferré, Rosario

(n. 1942). “Amalia” (Huellas 715-727). |

|

|

9

de marzo |

Sklodowska, Elzbieta. “Descolonización

del canon” (Huellas 730-31); Retamar,

Roberto Fernández (n. 1930). “Calibán”

(Huellas 741-48); Menchú,

Rigoberta (n. 1959). Me

llamo Rigoberta Menchú

y así me nació la conciencia (Huellas 749-62) |

|

|

Semana 10 |

Presentaciones cortas de tópicos para composición #2; presentación de 5-8 minutos |

|

|

14 de marzo |

Estudiantes: Por

favor seleccionen un día. |

|

|

16

de marzo |

Estudiantes:

Por favor seleccionen un día. |

|

|

Semana 11 |

Final Exam: Tuesday,

March 21: OJO: Before coming to class please have the following ready: 1.

Versíon más reciente; 2. Propuestas

anteriores. 3. Please

fill out “Checklist for Writing Papers [. . .]” (last page of syllabus). Instructor won’t read compositions if any of

these elements are missing. |

Entregar composición no. 2. |

L.V.C.O.M.

RUBRIC

EVALUATION

CRITERIA FOR

ALL COMPOSITIONS*

Language 25%

12 VERY

POOR: Many errors

in

use and form of the grammar presented in lesson; frequent & basic

errors in

subject/verb agreement; non-Spanish sentence structure; erroneous use

of

language makes the work mostly incomprehensible; no evidence of having

edited

the work for language; or not enough to evaluate.

16 FAIR

to POOR: Some

errors in the grammar presented in

lesson; some errors in subject/verb

agreement; some

errors in

adjective/noun agreement; erroneous use of language often impede

comprehensibility; work was poorly edited for language

21 GOOD

to AVERAGE: Few

errors in the grammar presented in lesson;

occasional errors in subject/verb or adjective/noun agreement;

erroneous use of

language does not impede comprehensibility; some editing for language

evident

but not complete

25 EXCELLENT

to VERY GOOD: No errors

in the grammar presented in lesson; very few errors in subject/verb or

adjective/noun agreement; work was well edited for language

Vocabulary 20%

8

VERY

POOR: Inadequate; very repetitive; incorrect use or non use of

words

studied; literal translations; abundance of invented words; or not

enough to

evaluate. Reader does not understand.

12

FAIR to POOR: Erroneous

word use or choice leads to confused

or obscured meaning; some literal translation and invented words;

limited use

of words studied, repetitive. Reader has

many difficulties to understand.

16

GOOD to AVERAGE: Adequate but

not

impressive; some erroneous word usage or choice, but meaning is not

confused or

obscured; some use of words studied.

20

EXCELLENT

to VERY GOOD: Broad; impressive; precise and effective word use

and choice;

extensive use of words studied.

Content (use of evidence and argumentation)

35 %

|

23

VERY

POOR: Series of separate sentences with no transitions;

disconnected ideas;

no apparent order to the content; or not enough to evaluate, very

repetitive.

Reader gets lost.

27 FAIR

to POOR: Limited

order to the content; lacks logical sequencing of ideas; ineffective

ordering;

very choppy; disjointed; and repetitive.

31 GOOD

to AVERAGE: An apparent order to

the content is intended; somewhat choppy; loosely organized but main

points do

stand out although sequencing of ideas is not complete.

35 EXCELLENT

to VERY GOOD: Logically

and effectively ordered; main points and details are connected; fluent;

not

choppy whatsoever.

Organization 15 %

6

VERY

POOR: Minimal

information; information lacks substance (is superficial);

inappropriate or

irrelevant information; or not enough information to evaluate

8

FAIR to POOR: Limited information;

ideas present but not developed; lack of supporting detail or evidence.

10 GOOD

to

AVERAGE: Adequate

information; some development of ideas; some ideas lack supporting

detail or

evidence.

15

EXCELLENT

to VERY GOOD: Very complete information; no more can be said;

thorough;

relevant; on target.

Mechanisms

(MLA; in-text citation) 5 %

1

VERY

POOR: no

mastery of conventions, dominated by errors of spelling, punctuation,

capitalization, paragraphing, handwriting illegible, or not enough to

evaluate.

3

FAIR to

POOR: frequent

errors of spelling, punctuation, capitalization, paragraphing, poor

handwriting, meaning confused but not

obscured

4

GOOD to

AVERAGE: occasional

errors of spelling, punctuation, capitalization, paragraphing, but meaning is not obscure

5

EXCELLENT

to VERY GOOD: demonstrates

mastery of convention, few errors in spelling, punctuation

2

Floating points for outstanding innovative work

*f.

Prof. Eva Núñez, “Rubrics.”

The

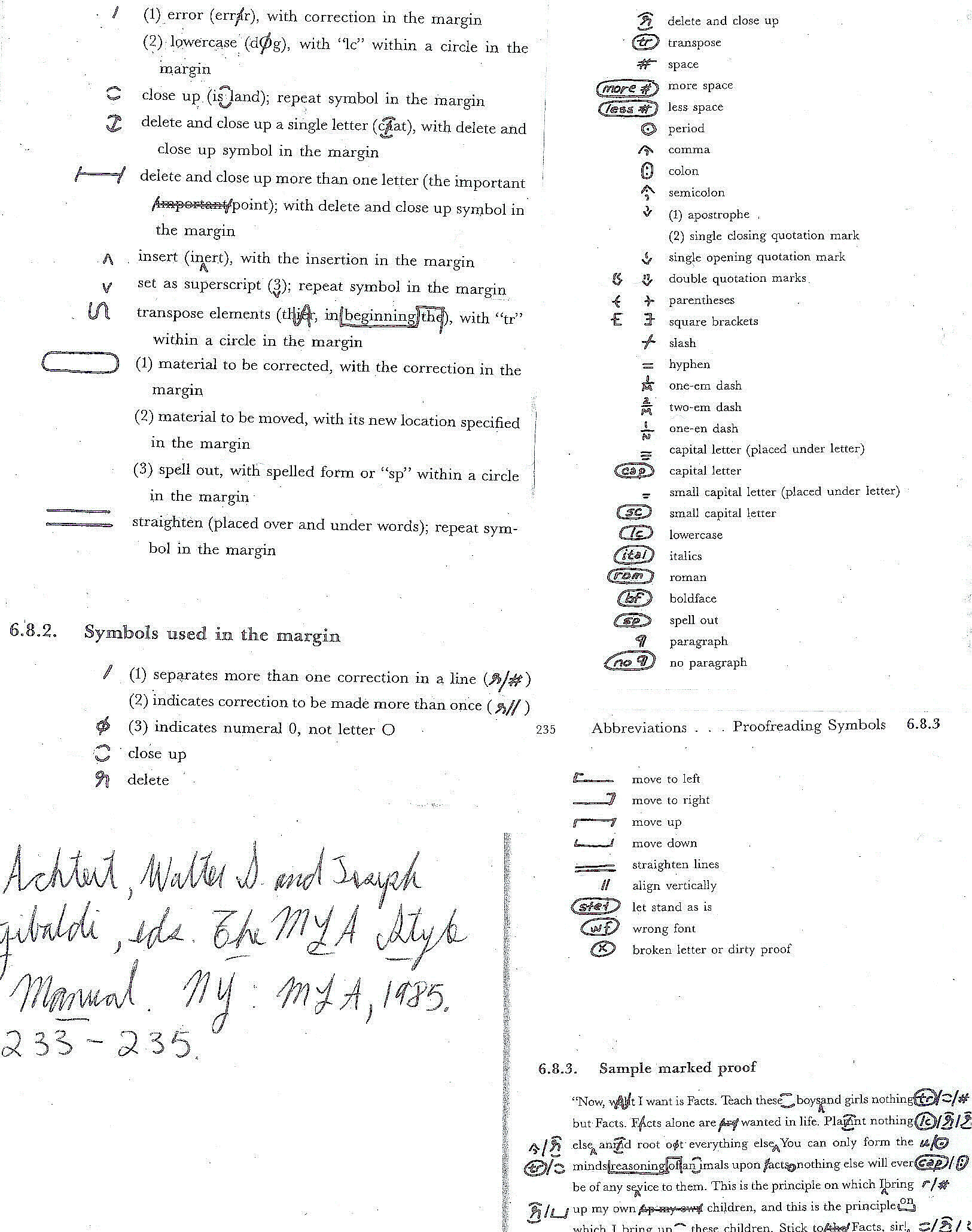

Proofreading Symbols

Lista de errores frecuentes

|

Using

uppercase in Spanish titles (only uses caps for proper names and the

first word of titles) |

Spanish: Violencia

juvenil en “La sandía” de Enrique Imbert English: Teen Violence in Enrique Imbert’s

“La sandía” |

|

Upper and

lower case |

los

Estados Unidos, EE.UU.; Obras citadas |

|

Diacritics/tildes |

*anos: anus; años: year *solo:

alone (estoy solo);

sólo: only

(sólo/solamente como manzanas) *mas: but

(Iré a Europa mas tendré que recaudar más dinero); más:

more (¡Quiero más pastel!) |

|

Anglicismos |

*“factos”=hechos *“más

peor”=worse. Use only

peor (La nieve fue peor que el año pasado) *Este

papel demuestra (wrong): essay

= ensayo; papel= physical

paper or

role=> El papel

de Superman fue dado a XY. *Work of criticism = la crítica; a critic

= el crítico Derrida (hombre) o la

crítica feminista Cixous (mujer) *Género

= gender and genre (so specify: los papeles genéricos (gender

roles)//El género literario |

|

Numbers |

50 cents in

English: .50 50 cents in

Spanish: ,50 Buck fifty in

English: 1.50 Buck fifty in

Spanish: 1,50 |

|

Masculine nouns,

article el/los, un/unos |

cuento, poema, artículo, trabajo,

verso, párrafo, tema, argumento, artículo crítico, personaje,

periódico, libro, correo electrónico, crítico (the

being writing

it) |

|

Feminine nouns,

article la/las, una/unas |

novela,

investigación, composición, entrevista, obra teatral, crítica, evidencia,

trama, revista, página electrónica, crítica (the work itself) |

|

Empty words

to avoid |

“cosa”;

“fuerte” |

|

Prepositions |

“Don’t

end sentences

prepositions with”: El estudiante

argumentada clase en. |

|

In-text Citation |

(Smith 33),

(“The Name of my Article in quotes” 33), (The Book Title in Underline

33) or (The Book Title in Italics 33) |

|

Use italics when words do not have an apt translation |

La

teoría queer

sobre literatura . . . |

|

Parallel verb

constructions in long sentences |

Wrong:

Al

niño le gusta comer manzanas y le encanta comió pasteles. Better:

Al niñó le gusta comer manzanas y le encanta comer

pasteles. Both sentences now

have verb

+ infinitivo |

|

When quoting

secondary sources |

Unless it is from a interview, avoid the “decir” (Cervantes dijo que su obra Don

Quijote es muy buena) and instead use: destacar,

apuntar, argumentar, concluir, subrayar, analizar, etc. |

|

Time to add

your personal favorite errors: Insert more

errors on the right column you need to avoid. See

problems from work you have recently received. YES, do write

them. Check this page often as you

complete all your writing projects. |

|

Using T.E.A. to Build a

Persuasive

Paragraph*

A

sample paragraph:

[1]While

globalization benefits large corporations, it creates a cycle of

underemployment

for low wage workers. [2]According to

Bob Smith, lead economist for the Institute for Economic Advancement,

“Globalization has resulted in continued corporate growth, while the

adjusted

wages for the average worker will continue to fall at a rate of 2.3 %

per year”

(Jones 26). [3] Smith's observation

shows that the economic benefits of globalization do not trickle down

to the

average worker. The actual buying power

of a low wage earner decreases as a result of this economic structure.

How to

understand this

persuasive paragraph using T.E.A.:

T.... Thesis, topic, theme:

[1]

·

Introduce

each paragraph

with a topic sentence.

·

Ask

yourself, “What point do

I want this paragraph to prove?”

·

The

topic of the paragraph

should be a key point to support your thesis.

Ex:

While

globalization benefits

large corporations, it creates a cycle of underemployment

for low wage workers.

E....

Evidence: [2]

·

Use

examples from your

research to prove the point of your paragraph.

·

Introduce

the source of your

evidence.

·

Use

citations so the reader

knows where your evidence comes from.

Ex: According

to Bob Smith, lead economist for the Institute for Economic

Advancement,

“Globalization has resulted in continued corporate growth, while the

adjusted

wages for the average worker will continue to fall at a rate of 2.3 %

per year”

(Jones 26).

A.... Analysis: [3]

·

EXPLAIN

how the evidence you

used supports your topic sentence.

·

Remember—the

quote or

example DOES NOT speak for itself. Your

job as the writer is to draw connections for the reader.

·

Use

phrases such as these: shows, this demonstrates or this is

an

example of...

These tells the reader you

are about to draw conclusions/make connections.

·

REMAIN

IN 3rd

PERSON!! You can clearly express your opinion without

saying “I think.”

Ex:

Smith's

observation shows that the economic

benefits of globalization do not trickle down to the average worker. The actual buying power of a low wage earner

decreases as a result of this economic structure.

*f. Julie Veltman,

“History 10,”

Usos

de puntos suspensivos [ . . .] y de [ ]

Ariel (1900) by José Enrique Rodó

is our primary text:

Al

conquistar los vuestros, debéis empezar

por reconocer un primer objeto de fe, en vosotros mismos.

La juventud que vivís es una fuerza de cuya

aplicación sois los obreros y un tesoro de cuya invención sois

responsables

(Rodó 353).

- When using ellipsis or

brackets when quoting from source’s primary sentence:

Wrong model: En Ariel

Rodó le indica a las jóvenes de naciones latinoamericanas que tienen

que

reconocerse como personas importantes en su historia “Al

conquistar los vuestros, debéis empezar por reconocer un . . . objecto

de fe . . . en vosotros

mismos” (Rodó 353).

Better model: En Ariel

Rodó le indica a las jóvenes de naciones latinoamericanas que tienen

que

reconocerse como personas importantes en su historia “[a]l

conquistar los vuestros, debéis empezar por

reconocer un [. . .] objecto de fe [

. . .] en vosotros mismos” (Rodó 353).

OJO: see problems with capitals, with preserving original punctuation, and with too many [ . . .] in one sentence

Even better model: En Ariel Rodó le indica a las

jóvenes de naciones latinoamericanas que tienen que reconocerse como

personas

importantes en su historia “[a]l

conquistar los vuestros, debéis empezar [. . .]

en vosotros mismos” (Rodó 353).

- When using ellipsis and/or

brackets when quoting between two or more sentences from source:

Wrong model: En Ariel

Rodó le indica a las jóvenes de naciones latinoamericanas que tienen

que

reconocerse como personas importantes en su historia al destacar lo

siguiente: “Al conquistar los vuestros, debéis

empezar por reconocer un primer objeto de fe, en vosotros mismos

. . . cuya invención sois

responsables” (Rodó 353).

Better model: En Ariel Rodó le indica a las jóvenes de naciones latinoamericanas que tienen que reconocerse como personas importantes en su historia al destacar lo siguiente: “Al conquistar los vuestros, debéis empezar por reconocer un primer objeto de fe, en vosotros mismos. [. . . ] cuya invención sois responsables” (Rodó 353).

Rules of Thumb:

*[Brackets] means

that you as

a writer are inserting information that is not in the original source

material.

*Preserve in your

essay the

meaning of the source: avoid too many [ . . .] or brackets.

*Preserve the punctuation of source by using brackets to preserve original sentence (s).*IF ORIGINAL SOURCE has [ . . .], there is no need to use brackets. In a parenthesis, you may want to clarify its use: (ellipsis in original; puntos suspensivos en el original).

Checklist for Writing Papers

in the

Humanities

As you are

completing your

essay, please make sure you consciously perform the following tasks. Your final grade will be based on ALL of the

following components (also see “LVCOM,” our essay-evaluation rubric). Please check each item off as your complete

your essay. OJO:

Instructor may stop reading

your essay if errors that were corrected in proposals or earlier

versions of

the paper were repeated in your current version. If

this should occur, the essay’s grade will

be based on section that was read or, if applicable, the grade will

remain the

same as before (for students working on revisions of their work).

Thesis

& Title

¨ Do I have a thesis?

¨ Have I clarified my

thesis?

¨ Have I placed limits

to my thesis?

¨ Does the title

reflect the thesis?

¨ If using works of

fiction, did I mention them in my thesis statement?

¨ Please draw a box

around your thesis statement.

Transitions

between Paragraphs and Topic Sentences

¨ Did I create organic

transitions between paragraphs that allow one paragraph to “flow” into

another?

¨ Do my paragraphs

directly relate to my thesis?

¨ Please draw a box

around topic sentences. Topic sentences

are the main sentences for each paragraph.

Topic sentences are the mini-thesis for each paragraph and

answer a

component of your thesis.

¨ In the right margin

for each paragraph and next to your topic sentence, please write the

one word

(in Spanish or English) that best describes the point of this topic

sentence

and paragraph.

Citing

Sources

¨ Does the essay have

secondary sources?

¨ Do the secondary

sources fit your thesis?

¨ For the purposes of

this class, keep citations in languages other than Spanish in the

original

language. In short, you do not need to

translate quotes into Spanish. Exception: Graduate students are expected to provide

translations into Spanish OR quote from published translations.

¨ In citing sources, I

always introduce the source and its author:

En Abnormal Psychology, Cromer argumenta

que el personaje

de Othello

de Shakespeare culpa a la luna

por su comportamiento: “She

comes more near the earth than she was

wont / And makes men mad” (666).

¨ In citations longer

than five lines, I have set the quote separate from the sentence, have

maintained a double space and have given proper page number:

XXX Part of a long paragraph XXXXX René de Costa provee un resumen

del estilo

de Ruben Darío:

XXX Pretend that there are

five lines of text and that

it is double spaced.XXX

Y todo eso es

una prosa rica y

fluida, poblada de metáforas. (Huellas 325)

MLA

convention

¨ Did I double check

the Obras citadas

page for

MLA citation problems?

¨ Are the margins

correct for this page (is there a tab in the second line, for example)?

¨ Is my last name on

each page?

Grammar

¨ For the first five

lines of your essay, please draw a box around the subject. Model:

Esta composición demuestra como Don

Quijote es

una crítica de las novelas de caballería.

Italics = box

¨ Please draw a circle

around the main verb. Italics = circle

Esta

composición demuestra como Don

Quijote es una crítica de las

novelas de caballería.

¨ Did I correct all

grammar problems that appeared in earlier drafts?