| Leslie S. Dodge – bioinfo |

last modified: |

Dodge's books and some internet research furnish at least a few facts about him.

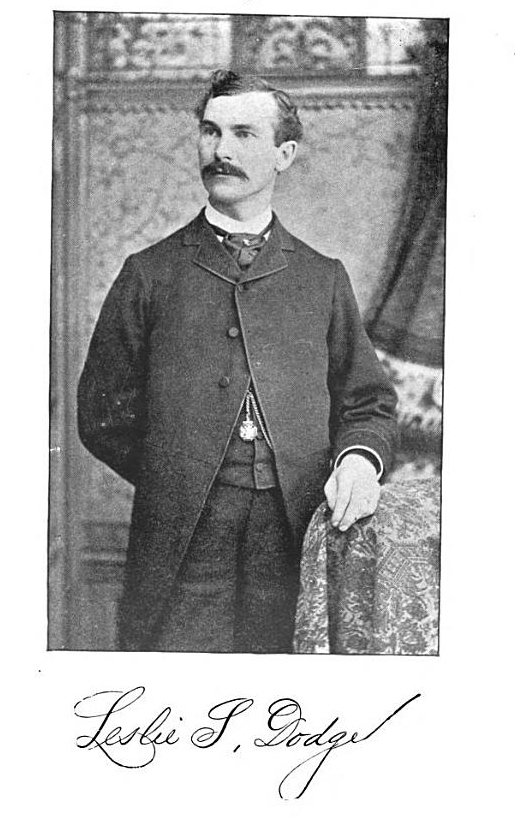

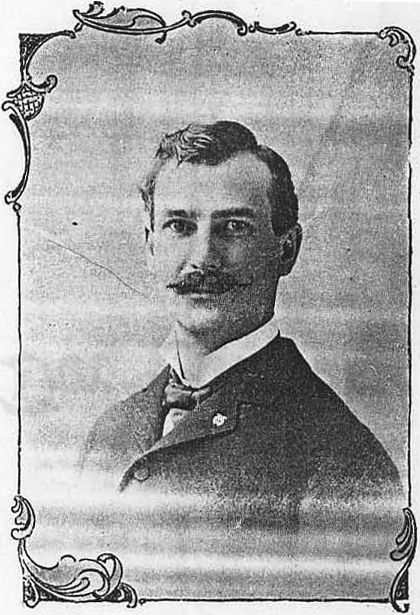

The endpapers furnish several portraits, from several decades of Dodge's life (though of course the date of the book may not match the date of the image):

|

|

|

|

French book, 1896 edition |

German book (but from a late edition) |

ca 1912 |

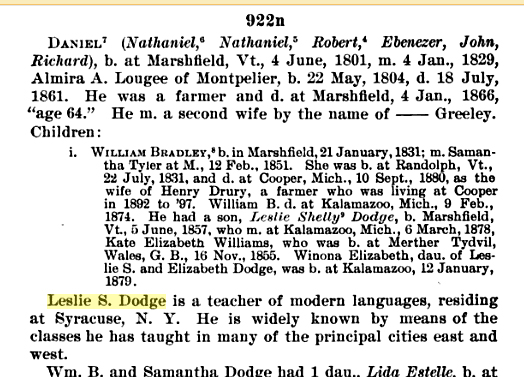

GoogleBooks furnishes this excerpt from the Dodge family history, which provides the middle name of "Shelly" and gives us a birthday of 5 June, 1857, and tells us that Dodge married Kate Elizabeth Williams, of Great Britain, on 6 March of 1878:

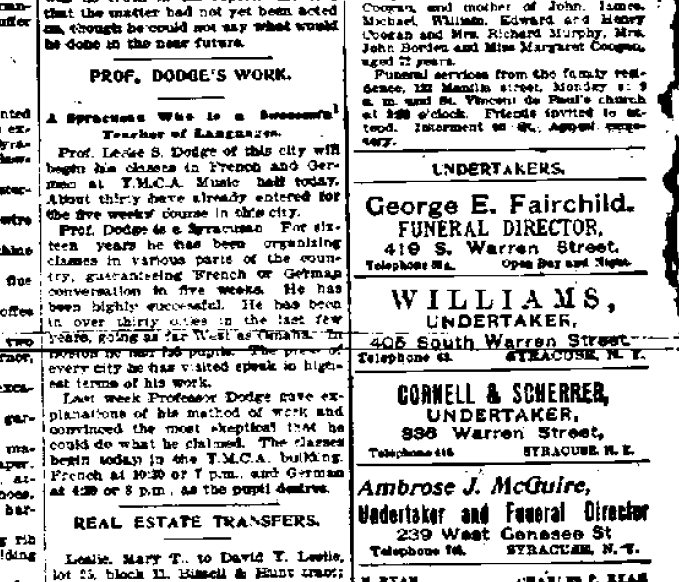

An article in the 21 September, 1896 issue of the Syracuse Courier (below left) says that Dodge will be teaching French and German there, and that he has been teaching for 16 years, that is from 1880, when he was 23. (The endpapers to the 1897 edition of his intro German textbook say "Established 1881".) The title of "Professor" need not be taken as proof of an academic position or, much less, and indication of a college/university education, though that could well be supposed from the nature of Dodge's occupation and the books he wrote - and yet again, the books and method are not at all typical of a college environment. But we can be fairly certain that Dodge's books were not used in college language instruction.

|

An earlier article, in the Trention Times of 17 November, 1888, is pretty much a fluff piece, but it shows that Dodge was established as an itinerant language teacher by age 31, and had already published his introductory German textbook for use in his classes.

I have not yet found a death date for Dodge. Given the close linkage between Dodge, his method, and his books, we might take the year of the latest edition of any of his textbooks as establishing that Dodge was still alive then. The Dodge genealogy book provides no help here, since it ends in 1898. The thrid edition of Das praktische Handbuch was published in 1915, and that is the last edition listed in worldcat.org. There appears to be no other edition of any of Dodge's books beyond that year either. (Worldcat.org does give us "Shelley" (rather than the genealogy's "Shelly" as Dodge's middle name, which adds a certain academic-romantic flavor.)

Other than Dodge's death date, we are left wishing to know: How did Dodge himself learn German and French? When did he travel to Europe? What did language lessons cost around 1900? Did college professors teach on the side? Certainly there is a history of science professors doing public lectures for fees, but teaching languages is another matter, and a college would probably not want its faculty traveling from city to city, specially during the academic year. Whatever the case, when Dodge was on the road he was a busy man. He not only had to set up his courses by doing advance publicity and arranging for facilities; according to the Syracuse Courier article (above left), on a given day he might teach French at 10:30 am and 1 pm, and then German at 4:30 pm and 8 pm.

Picclick.com, a site that sells minor memorabilia from bygone times, lists several items related to Dodge - not only his books, but also some illustrations. Not surprising are ones of Paris, Berlin, and Helgoland. There is a suggestion of some link to Jerusalem, and one of the Berlin illustrations is of the Omar Mosche (Mosque) there. And in Dodge''s intro German textbook some of the later chapters, rather improbably for a German book, ahve sections about "Palestine", "A Trip to Jerusalem", and egypt (as well as Paris, Edinburg, and - quite plausible as travel destinations for Dode, though unusual as content in a German textbook - New York, Niagara Falls, the Lick Observatory). Professor Dodge would not be unusual among textbook authors in exploiting his touristry as textbook content, though at the time there was no provision for deducting such trips from ones income tax.

So who was Dodge? Objectively, and in terms of his individual life, he was an intinerant language teacher with a claim - no doubt essential to his success - to being some sort of intellectual with a globe-trotting cultivation. Within a larger cultural framework, and a very colorful part of the American identity it is, Dodge was but one of a horde of such purveyors of learning and "finish", whether legitimate or otherwise in their claims about themselves and what they sold. As one historian has put it, "hustle" (and the "hustler") were key features of 19th-Century America, in both positive and negative senses. (And our own age is one of self-improvement gurus and books!) Dodge might be compared to that fictionarl and famous itinerant seller of learning materials and lessons, Professor Harold Hill of The Music Man, who purveyed band instruments, uniforms, and his "method" to the aspiring middle class of the same time. And I suspect that there is more than a little of Dodge and Hill in many a progressive language teacher. I know that's true of me - Harold Hill is my chief metaphor of myself as a language teaching profes