![]()

Note:

This page is adapted from information available at the Colonial Albany Social

History Project's website. On

the World Wide Web at http://www.nysm.nysed.gov/albany/albanycongress.html

![]()

The Albany Congress met

in Albany New York from June 19 to July 11, 1754. Holding daily meetings at

the City Hall, official delegates from seven colonies developed strategies

for Indian diplomacy and considered Ben Franklin's Albany

Plan of Union. Unsure of its authority to participate, the province of

New York sent only an unofficial delegation, which included Lieutenant Governor

James De Lancey and two men with strong Albany connections, William

Johnson and Peter Wraxall. The Iroquois Confederacy and other Native groups

were represented at the meetings as well.

The Albany meeting site proved Albany's importance as the last outpost of European-style civilization before the frontier - a place where settlers, officials, and native peoples had and would continue to come together to consider items of mutual concern. The meetings brought Benjamin Franklin and other important Americans to Albany - opening up the community to the outside world. The trip was instructive for many of these colonial leaders.

Over a month of intensive activity, the convention gave notoriously insular Albany people ranging from the city fathers to the rank and file citizenry their first prolonged contact with other Americans whose cultural heritage was substantially different from their own. For all concerned, the summer of 1754 provided memories and lessons that many of them would not forget.

![]()

Albany's Beginnings

In New York State, the first city to be so designated an actual city was New York City; it received a royal charter in April 1686. Albany, with a population of about 500 people (one-fourth the size of New York City), received its municipal charter from Governor Thomas Dongan three months later on July 22, 1686. The so-called Dongan Charter incorporated Albany, fixed its boundaries, set-up a municipal government, and endowed the city corporation with a number of special rights and privileges.

Albany's essential nature was commercial. Initially, the community economy was based on the fur trade. By 1686, Albany was evolving into a place where regional farmers bartered their crops and forest products for imported and locally crafted items; where they came to have tools and other things repaired; and where they found spiritual and legal guidance. By that time, city people had begun to divide into business, production, and service enterprises - although most Albanians engaged in some of all three activities. The Dongan Charter further enhanced Albany's status and the English fort provided the community with its first great government enterprise.

The fledgling community granted a city charter in 1686 was in reality a town of about 120 buildings - clustered together city-style and encircled by a tall, wooden stockade. Seventeenth century Albany had four principal public buildings. The city hall was located near the water on Court Street; the Dutch Reformed Church set in the middle of the city's main intersection; a smaller Lutheran Church which often was without a pastor; and a more imposing wooden fort located farther up the hillside and overlooking the community.

By the time of the Albany Congress, the city of Albany boasted a population of over 1,000.

![]()

The City of Albany

By

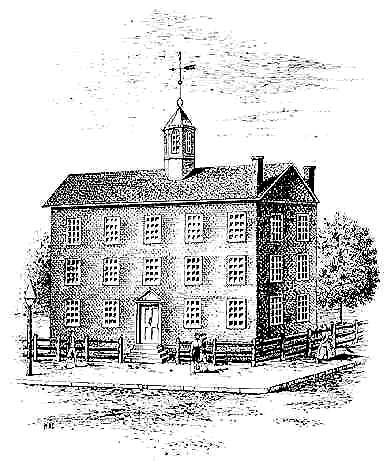

the 1730s, the city fathers, the clerk and the sheriff were complaining that

the now old Stadt Huys city hall was inadequate to serve a growing city and

county. In 1738, Albany successfully petitioned

the provincial government for funds to build a new "City Hall which was

very much needed." In 1741, Albany erected a much more substantial building

on the same location. The new city hall was a large but plain brick building,

three stories high, with a steep-pitched roof. The bell in its belfry was

rung each day at noon and at 8:00 p.m. After the church and fort, it was the

largest structure and stood out on the Albany skyline. The Albany Congress

met there in 1754.

By

the 1730s, the city fathers, the clerk and the sheriff were complaining that

the now old Stadt Huys city hall was inadequate to serve a growing city and

county. In 1738, Albany successfully petitioned

the provincial government for funds to build a new "City Hall which was

very much needed." In 1741, Albany erected a much more substantial building

on the same location. The new city hall was a large but plain brick building,

three stories high, with a steep-pitched roof. The bell in its belfry was

rung each day at noon and at 8:00 p.m. After the church and fort, it was the

largest structure and stood out on the Albany skyline. The Albany Congress

met there in 1754.

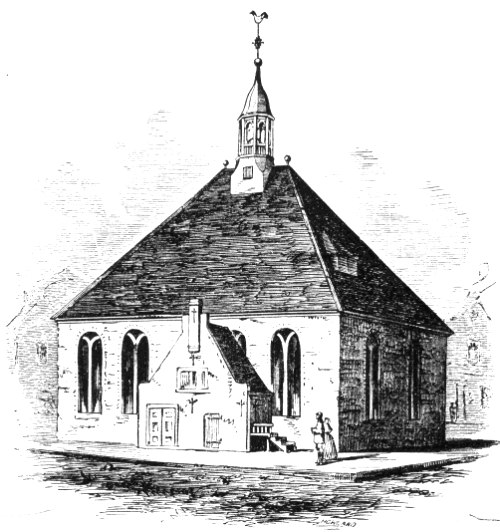

The

Dutch Reformed Church was situated in the middle of the city’s main intersection

from the 1650s to 1806. Enlarged about 1715, it was one of the largest buildings

in colonial Albany. Staffed continuously by a European-born dominie or minister,

it represented continuity with the past and stability. Its lay leaders or

Deacons were the most prominent Albany businessmen and officials. Well-supported

by these civic leaders, by more ordinary city people, and by those in the

countryside until Reformed Churches were built in Schenectady, Kinderhook,

Catskill, and Schaghticoke, the Albany Dutch Church also provided poor relief,

buried the dead, sponsored missionary work among Native peoples, and often

served members of other congregations whose houses of worship were less well

established. Regardless of ethnicity, most early Albany families received

some needed service from the Dutch Church.

The

Dutch Reformed Church was situated in the middle of the city’s main intersection

from the 1650s to 1806. Enlarged about 1715, it was one of the largest buildings

in colonial Albany. Staffed continuously by a European-born dominie or minister,

it represented continuity with the past and stability. Its lay leaders or

Deacons were the most prominent Albany businessmen and officials. Well-supported

by these civic leaders, by more ordinary city people, and by those in the

countryside until Reformed Churches were built in Schenectady, Kinderhook,

Catskill, and Schaghticoke, the Albany Dutch Church also provided poor relief,

buried the dead, sponsored missionary work among Native peoples, and often

served members of other congregations whose houses of worship were less well

established. Regardless of ethnicity, most early Albany families received

some needed service from the Dutch Church.

St.

Peters Episcopal Church grew out of a need to provide an English language

cultural center in still Dutch Albany. This long-standing Albany institution

had its roots in the 1690s when the Reverend John Miller was sent to serve

as chaplain to the English soldiers at the Albany fort. In 1695, Miller outlined

a plan for an Anglican ministry to serve and catechize

in Albany and beyond.

St.

Peters Episcopal Church grew out of a need to provide an English language

cultural center in still Dutch Albany. This long-standing Albany institution

had its roots in the 1690s when the Reverend John Miller was sent to serve

as chaplain to the English soldiers at the Albany fort. In 1695, Miller outlined

a plan for an Anglican ministry to serve and catechize

in Albany and beyond.

However, no minister was sent for almost a decade and the growing multi-ethnic population at Albany was served almost exclusively by the dominie of the Dutch Reformed Church.

The church pictured above, was built in 1731 of "very handsome stone . . . 58 feet in length and 42 in breadth" and sat in the middle of upper State Street and served Albany's Anglicans until it was replaced and removed in 1802.

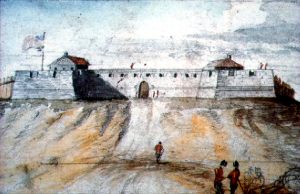

The

fort at Albany was re-built during the mid-1700's as part of a general

province-wide upgrade of fortifications. City taxes allocations supported

construction of stone walls, more substantial internal buildings, and improved

emplacements around the stockade perimeter as well. The watercolor by James

Eights shown on the right represents his mid-nineteenth century visualization

of the fort taken directly from a map made a hundred years earlier. The fort

reached its high point of grandeur during the French and Indian War when the

British army was encamped in Albany and the surrounding area. During that

occupation, the British further fortified the Albany structure and added external

barracks, magazines, storehouses, and a hospital.

The

fort at Albany was re-built during the mid-1700's as part of a general

province-wide upgrade of fortifications. City taxes allocations supported

construction of stone walls, more substantial internal buildings, and improved

emplacements around the stockade perimeter as well. The watercolor by James

Eights shown on the right represents his mid-nineteenth century visualization

of the fort taken directly from a map made a hundred years earlier. The fort

reached its high point of grandeur during the French and Indian War when the

British army was encamped in Albany and the surrounding area. During that

occupation, the British further fortified the Albany structure and added external

barracks, magazines, storehouses, and a hospital.

![]()

Soldiers

in Albany

By the mid 1670s, the British Duke of York was sending numbers of soldiers

to serve at the new fort built above what had become his settlement at Albany.

After New York became

a royal colony in 1684 (and particularly after 1691), the fort was garrisoned

by soldiers who were recruited in Europe and technically belonged to the British

army. They were, however, paid by the government of New York. These frontier

troops were part of what has become known as the "Four Independent Companies

of New York." These mostly foreign-born, "professionals" are

distinct from the citizen-soldiers who served in the

militia.

Several hundred young Britons came to the fort during the colonial period. Most of them moved on after their time spent at Albany. However, several dozen garrison soldiers settled in the community before 1776 - establishing English, Irish, and Scottish ancestry families in Albany for the first time. A number of these families persisted for several generations (and even permanently) in Albany.

For the most part, garrison duty at Albany was not a full time occupation. Some soldiers found ways to supplement their wages by working for local businesses or for themselves. Officers and enlisted men frequently boarded in Albany homes. These contacts led to relationships with local women that sometimes blossomed into families.

![]()

Indian Affairs in Albany

The Dongan Charter of 1686 gave the city corporation an exclusive right to interact with the native peoples inhabiting the lands north and west of Albany. That privilege was based on Albany's business connection to the Iroquois Confederacy and on the historical role played by the Albany fur traders as liaison between native peoples and provincial governments. Maintaining a working relationship with Native American hunters had been a cornerstone of Albany's success in the fur trade. A number of Albany traders understood native dialects and some were employed as interpreters.

As conflict with the French became inevitable during the 1680s, the English understood Albany's potential in first seeking to make allies of the Iroquois. Failing in that, provincial officials hoped Albany diplomats would be able to keep the Indians from joining with the French. That neutrality or arrangement has been known as the Covenant Chain of peace and friendship.

The core Commissioners of Indian Affairs (CIA) were the Albany city fathers. The mayor of Albany or the city recorder (deputy mayor) presided over business. Some aldermen and assistants seem to have been more active in Indian diplomacy than others - although the appointment of a corporation subcommittee is absent from the city records. The sheriff also was a member.

Sometimes garrison officers, local magistrates, and former members of the Albany corporation joined the commissioners at their meetings. However, the mainstay of the CIA was the board's secretary who was appointed by the royal governor.

![]()