(Slightly revised April, 2002)THE DECLINE OF NECESSITY,

THE INCLINE OF ILLUSIONA Weber State College Centennial Honors Series Lecture *

Presented on April 19, 1989

INTRODUCTION

In keeping with the tradition of the previous speakers who have commemorated

Weber State's hundredth anniversary in this year-long series, I have focused

on that ethical issue which appears the most fundamental and challenging

from my particular viewpoint. I frame this issue in the present tense in the

form of one essential question: How should we conduct ourselves in this

world that we, as human beings, have irrevocably altered in fundamental and

irredeemable ways? Illustrating this very uncertainty, the editors of Time

magazine, in an issue devoted to the ecology of our planet published in the

last decade of the century just past, put the question in a disturbing

double entendre: "What on Earth are we doing?"

It befits my sociologist's perspective that this concern is broad and expansive, if not completely overwhelming. My approach this to formidable question is though a discussion of what I call social necessity. I will try to both explain and illustrate what I mean by social necessity, describe how it has changed, and finally explore what that change implies.

Historically, varieties of social necessity have always shaped people's behavior. Human behavior has been not only directed by, but dependent on such forces. However, in our modern age, especially in the post-industrial West, what might be best classified as the traditional forces of social necessity are in a state of serious decline. We might even say that social necessity is being "disinvented," before our eyes and as we speak. Modern societies are increasingly being confronted with the totally new and puzzling problem of how to reinvent and reassert new forces of social necessity.

THE NATURE OF NECESSITY

Expressed through the values, beliefs, and norms into which every person

is socialized, social necessity provides the context within which human life

experiences are embedded. You and I constantly encounter social necessity in

our everyday experiences as we are constrained or compelled to think, feel,

or behave in particular ways. Our experience of these constraints seems

rooted in the way the world actually is, and therefore social necessity is

considered to be, as sociologist Peter Berger suggests, "part and

parcel of the universal 'nature of things'."

Thus social necessity is something with which we are all intimately familiar, even if we don't know it. People have everywhere and always thought, felt, and behaved in certain ways because it was necessary that they do so. It is almost a truism in sociology that the central task of every society is to get people to feel they need (or even better, want) to do what they're going to have to do anyway. An indication of the success of this dynamic is found in the frequency with which we all invoke necessity to justify our behavior. ("I had to do it." " I had no choice." "If it was up to me I'd do it differently but it's not my say so.") By stipulating the conventions of human behavior and guaranteeing their certainty, social necessity frees individuals from having to figure out for themselves what to do each moment, in every situation, under all circumstances.

HUMAN NATURE AND NECESSITY

Our species has a long and ambivalent relationship with social necessity.

This relationship rests upon the very kind of animal we humans are. We have

been accurately described as the animal without a "natural"

nature, the animal that has no "species-specific environment," the

animal which is "under-specialized." Eric Fromm described the

human being as "the only animal who finds his

[1]

own existence a problem which he has to solve and from which he cannot

escape." "Unlike the other higher mammals, who are born with an

essentially completed organism," writes Peter Berger, "man is

curiously `unfinished' at birth. Man does not have a given relationship to

the world. He must ongoingly establish a relationship with it." We

humans must not only establish a relationship with the world, we must also

establish the world to which we will be related--the world of society and

culture.

And yet, as Berger observes, this world "appears to common sense as something quite different, as independent of human activity and as sharing in the inert givenness of nature." It is this apparent independence and inertness that give both society and culture the quality of necessity. Human beings thus take the world for granted as necessarily this way and not some other, and so the world becomes that to which they must conform. [2]

A USEFUL PARADIGM

Based on several years of research, a colleague and I have developed a

paradigm which is especially useful for understanding this inherent "givenness"

of human societies. Our paradigm identifies the three features essential to

all societies: order, meaning, and membership.[3]

These are the dimensions along which social necessity is always expressed.

In terms of these dimensions, all societies provide their members with a

stable frame of reference (order), a sense of purpose (meaning), and the

feeling of belonging (membership). In the absence of these elements,

cultures, societies, even organizations just don't work. So it follows that

if the social conventions of order, meaning, and membership are declining,

they must be resuscitated; if they are being disinvented, they must be

reinvented--or society itself will fail.

CHANGES IN SOCIAL NECESSITY

Although these three dimensions of social necessity are constants, their

historical content has changed over time. Three distinct phases of human

development can be identified across the broad sweep of history, each

characterized by a difference in the content of social necessity.

[4]

The first phase of human development extends from the dim mists of human prehistory to the advent of industrialization. The second phase is more or less congruent with the Industrial Revolution. The third phase, for which we do not yet have a name and with which we have not yet fully come to grips, is the central concern of this paper. The influence of this third phase is rapidly beginning to impact us, as I intend to demonstrate.

I can portray the difference in these three phases with a bit of word play on an old adage: "Necessity is the mother of invention." This familiar saying effectively describes the social necessity that characterized the first phase of human development. In this first phase the expressions of social necessity that shaped human behavior were determined almost entirely by physical nature. To revert to our sociological truism, what people needed to do resulted almost entirely from natural forces over which they had little or no influence.

In the second phase of human development invention became the mother of necessity. No longer was nature the mother of invention; rather it was industrial invention that mothered social necessity. What people needed to do in this second phase was increasingly determined by the complex of inventions, both material and social, which made up the Industrial Revolution. We are most familiar with and perhaps take most for granted this kind of social necessity, even as we complain about it and struggle against it.

But we are now beginning to find ourselves in a third phase of human development. In this third phase we have been brought face to face with a very disquieting challenge: that of having to reinvent or invent social necessity anew, consciously and directly, without either the guidance or the solace provided by the implacable forces of nature or the impersonal demands of industrialization.

ILLUSTRATING THE CHANGES: SEX ROLES

I can illuminate these three phases by drawing on material from a course

I team-teach (with Dr. Rosemary Conover) called "Sex Roles: Past,

Present, Future."

[5]

The changes in gender across these three phases illustrate corresponding changes in the

nature of social necessity.

Sex roles--what we might call the necessities of gender--were once almost entirely rooted in human physiology, a function of sex-linked biological attributes. For example, endurance in the female and upper body strength in the male led to a sex-linked division of certain kinds of activity--carrying for the female, throwing or leveraging for the male. To take another example, the almost continual pregnancy and lactation in adult females led toward their overall care of young children, while the absence of any biological connectedness to reproduction beyond the brief act of impregnation led males toward tasks such as hunting and warfare which required movement away from the domestic scene. There are a large number of similar sex-linked differences, both obvious and subtle. In situations where life was often nasty, mean, brutish, and short, any differential advantage given by sexual biology in meeting the demands of the physical environment were fully utilized in order to survive.

Things changed, quite radically and in a relatively brief amount of time, with the burgeoning of the Industrial Revolution, often acknowledged to be the single most dramatic transition in history. The Industrial Revolution imposed a whole new set of requirements upon males and females--sometimes congruent with their physiological capacities, many times not. What did take precedence were the instrumental demands of an industrial system characterized by machine power and rationally calculated relationships.

It is useful to distinguish between an early period of the Industrial Revolution, when the biological characteristics of sex were still significant, and a later period, when the very success of industrial and technological efficiency radically diminishes their relevance. Upper body strength, for example, was an advantage for a steam locomotive fireman who might shovel as many as 20 tons of coal during his daily run; rapid and precise hand and eye coordination was an advantage for a seamstress or a manual worker on a small parts assembly line. Today a person does not need any particular sex-linked physical capacity to pilot an airliner weighing 85 tons, to write a computer program, or to manipulate many large pieces of industrial equipment. Yet males and females are still differentially socialized in ways that reflect the sex role specialization of an industrial society, with male socialization tending toward the instrumental end of the spectrum and female socialization tending toward the relational. [6]

Success in eliminating the significance of gender differences introduces the dilemmas of the third, post-industrial phase. If what it means to be male or female is no longer necessitated by either the physical demands of the natural environment or the instrumental demands of industrial invention, what then does it mean to be male or female? With en vitro fertilization and "surrogate wombs", to say nothing of professional child care, females can now be distanced from their reproductive as well as their maternal roles, and with artificial insemination males can be even further removed from their already distant roles as fathers.

Thus in the case of gender, we are confronted with the need to invent new definitions of male and female. How should we behave as one or the other? How should we select from the wide assortment of gender-related traits? And why should we even to have to choose--why can't we all have it all?

THE OPEN-ENDEDNESS OF CHOICE

What is new here, and I want to be very clear about this, is the very

open-endedness of choice itself. In this social context, contemporary

psychologists may suggest the option of androgyny, an option which may have

very real attractions. But nothing compels the acceptance of such an option.

It carries little or no social necessity. It is an entirely elective choice,

which means that it can be taken for the most whimsical of reasons or for

the briefest moments of time. The order it offers may be fragile; the

meaning facile, the membership fleeting. It does not necessarily abide.

The decline and disinvention of social necessity which has prompted this new open-endedness of choice appears as a powerful subtext in many of the troubling issues now facing post-industrial societies. We live in such a society. Lacking deeply embedded conventions and a strong sense of tradition, the disinvention of necessity is perhaps more pronounced in the United States than in most other Western societies. Let me amplify this point with several more illustrations.

FIRST ILLUSTRATION: TIME AND THE DISINVENTION OF MEANING

Once time was given by the sun and the seasons. But industrial society,

with its need to coordinate a multitudinous and complex set of activities,

required a society-wide definition of time. In the U.S., for example, where

once every community maintained its own local time, a "standard

time" became necessary as railroads connected previously separate towns

across the country. Today, we need look no further than to our wristwatches

and "daytimers" for concrete expressions of this invented social

necessity.

But in the third phase of development, the industrial time of clocks and calendars actually becomes less definite and more elusive. For example, in the world of computers and electronic information, a difference exists between what has only recently come to be called "real time" and what might be referred to as "virtual time". [7] Immediate experiences of this difference are no further away than our own living rooms. Instant television replays seemingly allow the world to be done again, to be speeded up, or slowed down, or repeated as many times as one might wish. At increasing numbers of sports events, fans attend not so much to the actual play of the game as to instantaneous, often slow-motion, giant screen replays. They are thus electronically freed from the constraints of real time. The "live" television programs as well as delayed network broadcasts we receive at home can be manipulated still further by our individual use of VCR's; it is now possible to live our lives in "real time" while watching television programs in virtual time. Having already been set free from the necessities of natural time by the wonders of electric light, we are now able to escape, at least partially, from the necessities of industrial time through the newer miracles of electronic computers.

SECOND ILLUSTRATION: CHILDHOOD AND THE DISINVENTION OF ORDER

Modern childhood is a "social artifact" of the industrial

revolution, "not much more than one hundred and fifty years old."

[8]

As Neil Postman notes, pre-industrial societies made only two significant

age distinctions: infancy, which ended at about seven years, and adulthood,

which began thereafter.

[9] These two

categories were inherent in pre-industrial societies because everyone past

infancy had to work to ensure the group's survival. As the industrial

revolution raised the level of both productivity and the skills required for

employment, young people were gradually excluded from the workplace, and

childhood, a new social category running from ages seven to seventeen came

into being.

[10] Thus childhood, which

Postman calls "one of the great inventions of the

Renaissance,"[11]

became a social

necessity in the second phase of development.

Today, however, Postman argues that "childhood is disappearing, and at a dazzling speed." [12] Ironically, the values of individualism and personal worth which helped legitimate childhood now work to undermine it. A democratically inspired "children's rights" movement is striving to invest children with the same legal rights as adults, [13] while the electronic media are rapidly breaking down the control of knowledge which Postman and others argue is necessary to protect the innocence of childhood. [14] In addition, urban life and the demands of two-career and single-parent families tend toward a devaluation of childhood itself.

Thus, in the face of post-industrial forces, childhood, an invention of industrialization, is in decline. Unless some new necessity is invented to ensure its special status as a period of protected development, it may disappear altogether. [15]

THIRD ILLUSTRATION: AMERICANISM AND THE DISINVENTION OF MEMBERSHIP

Early in our history, people in this country began to move away from

their many and divergent origins toward a single unifying ideal, a national

identity. Whether religious, ethnic, national, or racial, most immigrant

groups desired to become more American. In the process, they subordinated

their other group identities to create a common sense of community. Today,

however, American society displays a different dynamic, one that is much

more fractionated. Newer immigrant groups do not aspire in the same way to

the old unitary ideal. Instead, they seem intent on maintaining the

character and qualities of their ethnic, cultural, and racial identities.

Once held together by a common, although often unspoken creed, America is

becoming increasingly multi-cultural, multi-ethnic, and multi-linguistic.

[16]

This newer expression of the fundamental democratic values of equality, individuality, and success [17] runs counter to the traditional ideal of E Pluribus Unum--"one out of many." And it tends toward the disinvention of America itself as a social necessity. Such a process may be inevitable. The irony is that the very values which required us out of necessity to forge a community, which we have held in common, and which have bound us together in the building of our society are themselves now at risk. [18]

UNDONE EVEN MORE BY THOSE WHO WERE SUPPOSED TO HELP

Thus the post-industrial societies of the West find themselves confronted

with questions that were once answered with little equivocation. In a past

that is not so distant, there was seldom occasion to pose many

questions--deeply necessitated social conventions provided answers before

consciousness could even formulate the questions. Yet few of us would

welcome back those earlier answers. [A woman's place is in the home. No work

is to done on the Sabbath. Don't question authority.] Seen from the broad

spectrum of alternatives now available, those answers are not very appealing

to the modern eye. But while they may not now be attractive, they were then

at least certain.

Once this decline of social necessity is recognized, a serious concern follows: Does the technological expertise and social insight produced by this third phase of human development provide any help? The response, from my perspective, is not very much.

Unfortunately, our increased technological and social capabilities have not been brought together in any way that has effectively forestalled the decline of social necessity. The one activity combining technology and social science that has been successful at inventing necessity--modern marketing--is neither socially redeeming nor morally encouraging. It has simply increased consumerism through the blatant exploitation of mass audiences.

One might seriously conclude then that in expanding choice and making life easier, technology has eliminated too much social necessity, and that the social sciences have revealed too much about how social necessity works. [19] Social scientists, after all, are responsible for much of the knowledge that explains why people and societies behave the way they do. It is social scientists who have not only confirmed that the emperor is naked, but have gone on to explain why people continue to think that he is "all bedecked in sweet finery."

Here is the hard post-industrial paradox. As individuals are freed from the constraints of social necessity they have to exercise much more choice. They are supplied with more alternatives but without the saving--and often salving--guidance of necessity. Culture's "unseen gods" [20] have vanished; convention's slights of hand have been revealed. The modern individual is existentially "thrown" into the universe; in Sartre's unrequiting phrase, we are all "condemned to freedom."

The demise of social necessity has been a covert theme in many of the issues addressed by the speakers in this series: questions about the social definitions of place, issues of reproductive behavior and the meaning of gender, questions about truth and lying and the subversive power of the electronic age, troubling insights into the workings of democracy and representative government, new and problematic decisions about life and death, humanness and personhood.

It is in regard to such issues that we might expect--especially of the social sciences--not only understanding, but solutions. But the fact is that the understanding provided by social science makes solutions much more difficult.

Ernest Becker, a scholar who was equally at home in anthropology, psychology, and sociology, reminds us that "social theory" has "the enormous task of understanding the very fictions that man performs in each society." [21] So it is inevitable that the social conventions which make social necessity effective would be revealed as fictions. Becker regards this as

self-exposure of a truly heroic kind, because, like all self-exposure, it [leaves us] nude and somewhat pitiful, thrown back to a position where [we can] no longer pretend. Little wonder...that very few have been able fully to digest this great achievement of sociological analysis.[22]

Little wonder that anyone would want to. But by virtue of their craft, sociologists have to. In so doing, they have made both social pretense and social insight much more troubling. In the words of Peter Berger, sociology has brought to consciousness "aspects of the world that are profoundly disturbing and a freedom that, in the extreme instance, evokes truly Kierkegaardian terrors." [23]

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE

The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus said that "for God all

things are good and right and just..."

[24]

If that is so, then what social necessity of truth will there

be to compel our common behavior? The eminent French sociologist Emile

Durkheim convincingly asserted that "there is no religion that is

false". If that is so, then what social necessity of ultimacy will

there be to compel common belief? Are we to simply let random circumstance

or collective convenience determine what is ultimate and true? And if that

is so, what will grant such arbitrary choices the social necessity to make

them bind and inspire?

But even if a foolish passion were desirable--and in the modern world many of them are destructive in too many ways--most, in fact, may no longer even be possible.

THE FUTURE IS AN ILLUSION

The fact is that, on the eve of the 21st century, circumstances in the

modern West have conspired to challenge us to invent, and to invent

conscientiously, a new and compelling social necessity. At the disquieting

forward edge of human history which we momentarily occupy, Western societies

have been finally thrust, both in celebration and in angst, face to face

with the problem of human awareness. Ernest Becker offers an incisive

summary:

In a short twenty-five hundred years since the beginning of Western civilization with the Greeks, man had discovered his own peculiar nature. He was the animal who created and dramatized his own meanings....If we were immodest, we could say that man's reason had finally given him the possibility of full possession of himself, to do with as he may. But it would be truer to say that evolution had brought life to the point of its greatest potential liberation. Or perhaps it would be most true to speak mythically in the face of this awesome and ill-understood achievement, and to say man had finally become a potentially fully open vehicle for the design of God. [25]

Human beings are highly interdependent; in modern society, this is more true than ever before. We cannot do without the formative and guiding constraints of social necessity as they are expressed through the human requirements for order, meaning, and membership. In the past we experienced social necessity as an imposed reality. Our newly acquired sophistication has enabled us to see through the social necessities of the past. Yet we have to recognize that human beings still require either the reality or the illusion of those necessities.

Thus we now know what we need: an illusion of social necessity that is not so closed as to preclude improvement nor so open as to deteriorate into delusion. [26] This suggests a new kind of social necessity, one that would fully reflect the human situation and express the human spirit, beneficently turning back upon its authors to sustain their potential.

The Western societies must find some way to deliberately design such an ennobling illusion of social necessity, simultaneously constructive, compelling, and correctable. I am not fully optimistic about the human capacity for "the design of God" in the world we now see before us. Yet it seems to me that our one true hope of social survival lies only in this direction. [27]

The poets alert us to how narrow is the path on which we find ourselves. On the one side, Emily Dickinson offers her caustic prospect in a brief four lines:

|

The Abdication of Belief Makes the Behavior small-- Better an ignis fatuus Then no illume at all. |

But "foolish passions" carry their own frightful dangers. Borrowing the words of William Butler Yeats--if the best lack all conviction and the worst are full of passionate intensity, we may well end up instead with some cruel substitute; some rough necessity, "its hour come round at last, slouching towards Bethlehem to be born." [28]

THE FINAL NECESSITY

That sounds like a fittingly dramatic finish. But I am inclined not to

end here. It is not enough only to give an account of the problem. So I want

to explain, at least briefly, the faint glimmer of illusion I see on the

horizon.

Over the past several months, as I have reflected on the issues surrounding social necessity, three themes have emerged; those of size, change, and connection. [29] These themes find expression for me in these three facts: first, that we live much of our lives in social entities that are too large for human habitation; second, that we are forced to get our bearings in settings where too much is changing too fast; and third, that much of the time we interact with other people in ways that are too brief and impersonal to foster sustained, felt connections. These facts have become especially critical in a world in which two dangers now eclipse all others: the threats to our planet of "ecological catastrophe or nuclear annihilation." [30]

In order to manage these concerns, the guiding illusion we must create will need to invoke and celebrate the qualities of smallness, stability, interdependence, and cooperation.

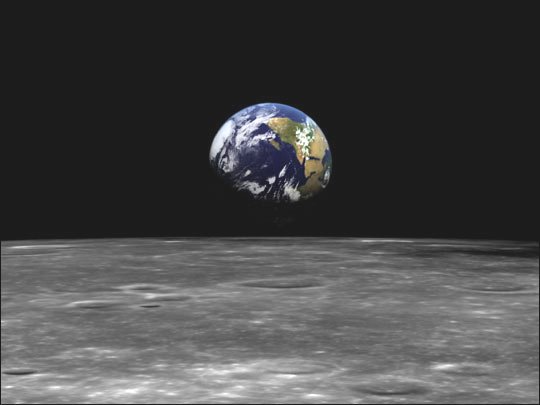

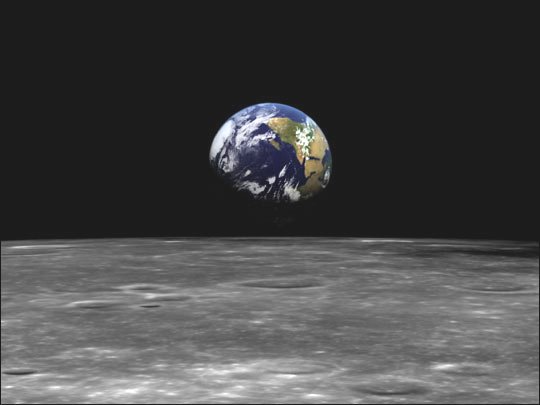

The twin prospects of ecological catastrophe or nuclear annihilation, as terrible as they might be, show us the way out, because they have something very much in common: the finiteness of the planet. Planet Earth has now become one eco-system and one social system. Ecologically and socially, the earth is a closed system, with fixed dimensions and upper limits to her carrying capacities, natural and human.

Given a world population of over 5 billion, increasing at a rate that will result in 6 billion people by the year 2000; given the grossly unequal world-wide distributions of wealth and poverty; given the current rate of destruction of natural resources by both the impoverished Third World and the over-developed West; given the existence of over 50,000 nuclear warheads (over two and a half tons of explosive for every man, woman, and child in the world)--given all this, it is stunningly clear that we have, in fact, reached a new limit, the final social necessity of the earth itself. We have achieved our one certainty. Since we humans are, in Joseph Campbell's felicitous phrase, "the consciousness of the earth," [31] so we must express the earth's necessity in a compelling illusion: Spaceship Earth, our Planet Home--

Gaia. Earthrise.

Planet Earth is much more tiny than ever we thought; it will survive only

if change is brought under control and managed wisely; we will prevail only

if we recognize that there is but one commons--our one common earth, our one

communal lifespace. Neither

we nor the commons will survive unless we do so together. The guiding

illusion we need, the one illusion which must compel social necessity now

and in the future, lies directly beneath our feet--we must lock it in our

imaginations, embrace it with our love, and--somehow--manage to come to believe in it with an

abiding faith.

ENDNOTES

*Subsequently published in in Great Debates and Ethical Issues: Weber State College Centennial Honors Lecture Series, Rosemary Conover and Ronald L. Holt (eds.). Ogden, Utah: Weber State College Press, 1989

1 I have tried to be sensitive to the gender bias of language in the body of this paper, but have retained quotations in their original form since, in my opinion, contriving to correct an author's writing would diminish the quality of expression.

2

As has been remarked elsewhere,

"...if a viable culture is one which provides satisfactory answers to

[Kant's four essential questions regarding human existence], then a truly

successful culture would be one in which the answers are so immediate,

complete, and reassuring that the questions themselves never intrude upon

awareness." See Michael A. Toth and Joseph C. Bentley,

"Discovering the Obvious: A Master Paradigm for the Social

Sciences," Social Sciences Perspectives Journal, Vol. 1, #1,

Proceedings of the 1986 Seattle Conference.

3

Our most complete explication to date is found

in Michael A. Toth and Joseph C. Bentley, "The Invention of Necessity:

Order, Meaning, and Membership", unpublished manuscript, n.d.

4 These three phases parallel the three phases

(biological, industrial, and cultural) identified in my paper, "The

Buffalo Are Gone: The Decline of the Male Prerogative," presented at

the Pacific Sociological Association, San Diego, California, April, 1982.

5 A full description of this course has been

published. See Michael A. Toth and Rosemary Conover, "Learning From

Within: Teaching an Interdisciplinary Course on Sex Roles", Social

Science Perspectives Journal, Vol.2, No.3, Proceedings of the 1988 NSSA

Portland Conference.

6 For a summary of these traits, see Michael A. Toth and Sherwin L. Davidson, "Lives Together, Worlds Apart: The Ties That Double Bind", paper presented at the annual meetings of the American Association for Marriage and Family Therapy, Dallas, Texas, October 1982.

Virtual time is "as if" time; it is as if it were real, but since it is not it does not have to obey the same rules, i.e., it can occur faster or slower than real time. Virtual time is time of technological convenience, made possible by the new processes of electronic information. An attempt at explanation, which comes from a computer technician, is contained in the following doggerel: "If it is there and you can see it, it is real; if it is there and you cannot see it, it is invisible; if it is not there and you can see it, it is virtual; if it is not there and your cannot see it, it is gone. A recent recognition of the potential confusion between different kinds of time occurred during the 1988 World Series in which some instant replays were attended by an announcement on the screen stating that the replay was being broadcast in "actual time".8 Neil Postman, The Disappearance of Childhood, New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1984, p.xi.

12 Ibid., p.xii. Postman is not the only person to make this argument. See, for example, David Elkind, The Hurried Child: Growing Up Too fast Too Soon, Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1981, and Edgar Z. Friedenberg, The Vanishing Adolescent, New York: Dell Publishing Co., 1959.

13 See, for example, John Holt, Escape From Childhood, New York: Ballantine Books, 1974.

14 This is the major thesis of Postman's book, op.cit., especially Part Two.

15 The full text of Postman's argument is as follows: "One might say that one of the main differences between an adult and a child is that the adult knows about certain facets of life--its mysteries, its contradictions, its violence, its tragedies--that are not considered suitable for children to know; that are, indeed, shameful to reveal to them indiscriminately. In the modern world, as children move toward adulthood, we reveal these secrets to them, in what we believe to be a psychologically assimilable way. But such an idea is possible only in a culture in which there is a sharp distinction between the adult world and the child's world, and where there are institutions that express that difference." Ibid., p. 15.

16 As Richard Rodriguez observed in regard to the bilingual schooling debate that marked the beginning of "middle-class ethnic resistance" to the process of assimilation in the 1970's, the bilingualists "do not realize that while one suffers a diminished sense of private individuality by becoming assimilated into public society, such assimilation makes possible the achievement of public individuality". (Richard Rodriguez, The Hunger of Memory, New York: Bantam Books, Inc., 1983, p.26.) The issue of bilingualism is, in its way, the linguistic counterpart to the tragedy of the commons. Similarly, the recent spate of legislation to make English the "official language" of the nation and its various states can be seen as an attempt to reinvent a common linguistic necessity.

17 I have drawn these values from Robert Bellah, et.al., Habits of the Heart, New York: Harper & Row, 1985, pp.22-26, in which are named, as the three primary American values, justice/equality, freedom/individuality, and success/achievement. This is obviously not an exhaustive list; there are other values, and they could be summarized in different ways. However, there is a tendency for such lists to be similar. For another example, see Theodore H. White, America in Search of Itself, New York: Warner Books, Inc., 1982, pp.99-102.

18 This is a topic difficult to discuss dispassionately, especially in the climate I have just described. One of the most challenging ironies of the disinvention of necessity not addressed in this paper is that liberals (to use the unfortunately inflammatory categories of political discourse) cannot identify, much less attempt to remedy these problems without appearing to be reactionary. Conservatives, on the other hand, simply remain conservative in their response to them. As Neil Postman laments in respect to a similar issue, "the only sizeable group in the body politic that has so far grasped the point is that benighted movement known as the Moral Majority." Those who are able to react in a manner consistent with their ideology are those who, from Postman's point of view, have the least attractive ideology. The liberals' dilemma is that if they are to remain true to their ideology they must stand aside as the system begins to burst apart.

19 Speaking to this point, John Rex, a former chair of the British Sociological Association, has stated quite bluntly that "sociology is at once the most important, the most troublesome, and the most dangerous subject in the university curriculum." See "The Trouble with British Sociology", New Society, May 25, 1978. In a similar vein, Peter Berger remarks that "people who like to avoid shocking discoveries, who prefer to believe that society is just what they were taught in Sunday School, who like the safety of the rules and the maxims of what Alfred Schutz has called the `world taken for granted', should stay away from sociology." See Invitation to Sociology, Garden City, N.J.: Doubleday Anchor Books, 1964, p.34.

20 The phrase is from Alan M. Kantrow, The Constraints of Corporate Tradition, New York: Harper & Row, 1987, pp.27-28. The full quotation is: "Over time, our awareness of artifice evaporates, leaving behind a residue that seems utterly matter-of-fact. It is this surface transparency, this invisibility, that gives conventions their special force in human affairs--in the how of how we think. Our culture has long known the power of unseen gods."

21 Ernest Becker, Beyond Alienation: A Philosophy of Education for the Crisis of Democracy, New York: George Braziller, 1967, p.131.

23 Peter Berger, "Sociology and Freedom", The American Sociologist, February 1971, p.3.

24 Quoted in Joseph Campbell, with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, Doubleday: New York, 1988, p.66.

25 Becker, op.cit., 1967, pp.148-149.

26 This statement paraphrases a comment of sociologist of religion, Paul Pruyser: "The great question is: If illusions are needed, how can we have those that are capable of correction, and how can we have those that will not deteriorate into delusions?" Quoted in Ernest Becker, Escape From Evil, New York: The Free Press, 1975, p.159.

27 Sociologists who have drawn this conclusion include Ernest Becker, Robert Bellah, and Peter Berger in works mentioned in the body of this paper. In addition, see Michael Harrington, The Politics at God's Funeral, New York: Penguin Books, 1985.

28 The reference, of course, is to William Butler Yeats' famous poem, "The Second Coming". See The Variorum Edition of the Poems of W. B. Yeats, New York: The MacMillan Company, 1957, pp.401-402.

29 Not surprisingly, the dimensions of order, meaning, and membership are clearly reflected in these three concerns.

30 Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade: San Francisco, Harper & Row, 1988, p.xiv.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ernest Becker, Beyond Alienation: A Philosophy of Education

for the Crisis of Democracy, New

York: George Braziller, 1967.

The

Birth and Death of Meaning, 2nd Edition, New York: The Free Press, 1971.

Escape From Evil, New York:

The Free Press, 1975.

Robert Bellah, et.al., Habits of the Heart, New York: Harper & Row,

1985.

Peter Berger, "Sociology and Freedom", The American Sociologist,

February 1971, pp.1-5.

A

Rumor of Angels, Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Co., Anchor Edition,

1970.

The

Sacred Canopy, Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday & Company, 1967.

Invitation

to Sociology, Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday Anchor, 1964.

Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann, The

Social Construction of Reality, Garden City, N.J.: Doubleday

Anchor

Books, 1967.

Joseph Campbell, with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth, New York:

Doubleday, 1988.

Freeman Dyson, Weapons and Hope, New York, Harper & Row, 1985.

Riane Eisler, The Chalice and the Blade, San Francisco, Harper &

Row, 1988.

David Elkind, The Hurried Child: Growing Up Too fast Too Soon, Reading,

Mass: Addison-Wesley, 1981.

Edgar Z. Friedenberg, The Vanishing Adolescent, New York: Dell

Publishing Co., 1959.

Eric Fromm, The Sane Society, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston,

1960.

Michael Harrington, The Politics at God's Funeral, New York: Penguin

Books, 1985.

John Holt, Escape From Childhood, New York: Ballantine Books, 1974.

Alan M. Kantrow, The Constraint's of Corporate Tradition, New York:

Harper & Row, 1987.

Robert Merton, Social Theory and Social Structure, New York: The Free

Press, 1957.

Neil Postman, The Disappearance of Childhood, New York: Dell Publishing

Co., 1984.

Richard Rodriguez, The Hunger of Memory, New York: Bantam Books, Inc., 1983.

Alfred Schutz, Collected Papers, Volume I: The Problem of Social Reality,

The Hague: MartinusNijhoff,

1967.

Time, January 2, 1989.

Michael A. Toth, "The Buffalo Are Gone: The Decline of the Male

Prerogative", presented at the

Pacific Sociological

Association, San Diego, California, April, 1982.

Michael A. Toth and Joseph C. Bentley, "Discovering the Obvious: A Master

Paradigm for the

Social Sciences", Social Sciences Perspectives

Journal, Vol.1, No.1, Proceedings of the 1986

Seattle Conference.

"The

Invention of Necessity: Order, Membership, and Meaning", unpublished

manuscript, n.d.

Michael Toth and Rosemary

Conover, "Learning From Within:

Teaching

an Interdisciplinary

Course on Sex Roles", Social

Sciences Perspectives Journal, Vol.2, No.3, Proceedings of the 1988

Portland Conference.

Michael Toth and Sherwin L.

Davidson, "Lives Together,

Worlds

Apart: The Ties That Double Bind",

presented at the annual meetings of

the American Association for Marriage and Family

Therapy, Dallas, Texas, October, 1982.

Theodore H. White, America in Search of Itself, New York: Warner Books,

Inc., 1982.

William Butler Yeats, "The Second Coming", The Variorum Edition of

the Poems of W. B. Yeats,

New York: The Macmillan Company, 1957.